2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Just as he had obsessed over the potential for nuclear war and self-destruction by the human race, Kubrick similarly became interested in the prospect of extra-terrestrial life. After reading everything he could on the subject, he decided to pair with acclaimed science-fiction novelist Arthur C. Clarke and adapt a film from his short story “The Sentinel.” While sci-fi films had had some popularity in the 1950s, often weaving Red Scare xenophobia into their plots and themes, a true masterpiece about space and space travel had yet to be made, and special effects technologies were still too rudimentary to adapt many stories to screen. But Stanley Kubrick’s meticulous production control was about to change all of that with what would become the apex of his career–and for some, of all of cinema: the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

With 2001, Stanley Kubrick crafted one of the most important landmark films in cinematic history. Its reputation and respect in the film community is well-known. Steven Spielberg said “The way the story is told is antithetical to the way we were accustomed to seeing stories.” Alfonso Cuarón called Kubrick’s work that of “someone who was very concerned with the language of cinema.” And Claire Denis spoke of the film’s unique approach to science fiction: “You knew it took place in space, but I didn’t expect that kind of strange reflection on humanity.”

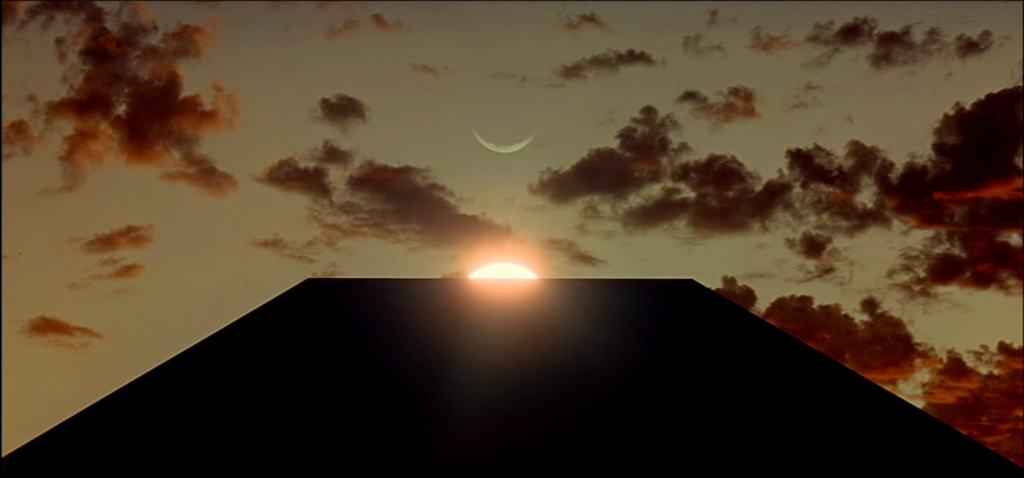

The screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey would consist of four segments, all connected together by the mysterious “monolith” which drives the human race into an evolutionary tumble. The opening segment begins with a grand shot of the Earth, Moon, and Sun in perfect alignment. Kubrick’s precise and exact framing is established from the start and his use of classical music revolutionary. Next, the “Dawn of Man” segment shows “man-apes” from four million years ago, struggling to survive and evolve among other predators and ape groups.

The first monolith inspires the “Dawn of Man”, in perfect symmetry

When the presence of the monolith placed in front of them by some unknown being introduces the idea of use a bone as a tool, the man-ape takes its place on top of the food chain, and the evolutionary process to what we know now begins. What is also discovered is man’s affinity for violence and death with said tools, and, as a consequence, the urge that would re-occur and plague society its entire existence. With the tumble in the air of a bone, Kubrick match cuts it with a satellite orbiting Earth, an advancement in storyline millions of years, and one of the boldest match cuts in film history.

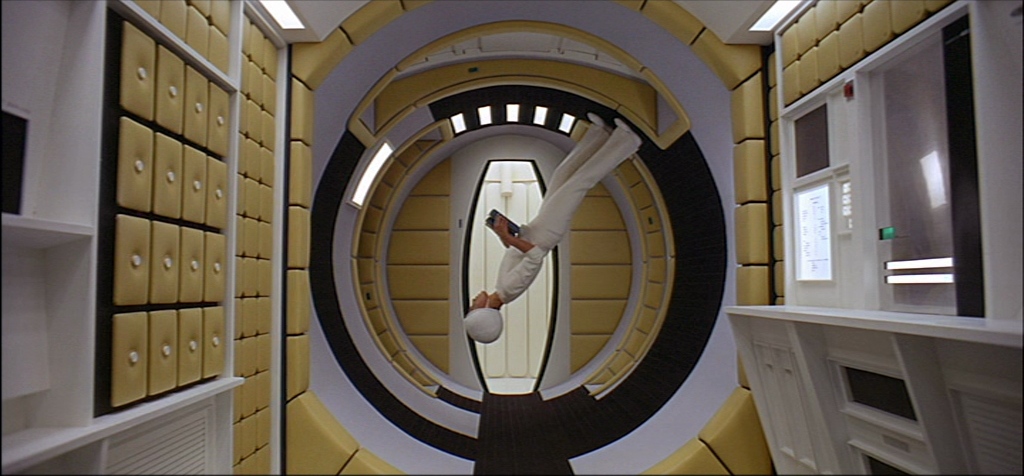

With more than a half hour of the film already passed, Kubrick shows the physics of space and space travel, as in the prior scene without dialogue. A Pan-American spaceplane carries Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) to the Space Station 5 for his mission to discover a monolith buried on the moon. The sequence is deliberately slow, with the mechanics of each shot and frame display a poetic feel of imagery. Space crafts float through the frame with The Blue Danube hypnotizing the audience. Long takes show the flight attendants carrying items throughout the space plane in centrifugal long shots.

Kubrick’s cinematography and set design at its most distinctive

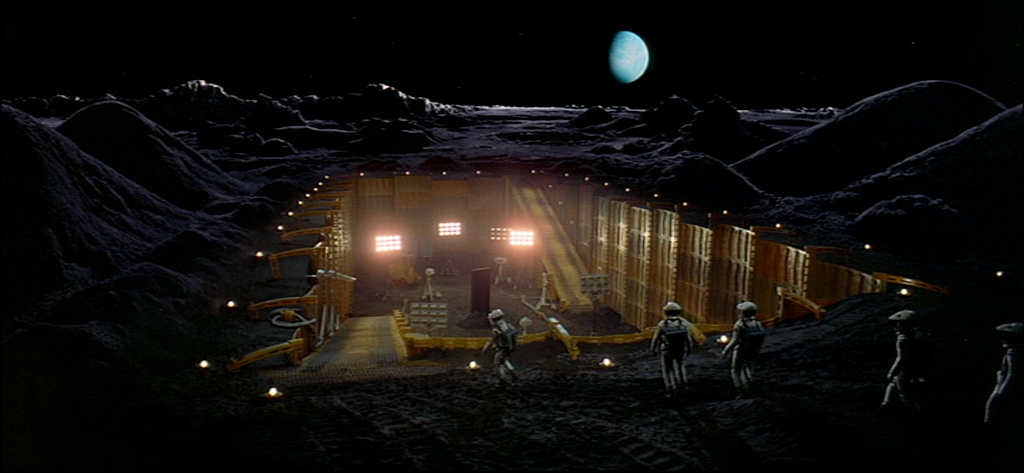

Half of the film’s dialogue is presented in this next sequence, as Dr. Floyd engages in small talk with the Soviets about his mission and his briefing to his crew about their upcoming visit to the monolith on the moon. When they finally arrive, the location is desolate and eerie, with large panels of light flooding the screen and the slow motion walk of the scientists accompanied by the morbid music of Requiem for a Soprano, the leitmotif for the monolith in the film. After the scientists touch the moon monolith, a high-pitched frequency is emitted from it and the scientists fail to stop it.

The 2nd monolith discovered on the moon shows Kubrick’s elaborate set design

The film abruptly enters its third act, set 18 months later on a mission to Jupiter (which we will later learn was where the moon monolith was sending the humans to the Jupiter monolith). On the space craft Discovery, Kubrick again slowly and deliberately shows the daily routines of scientists Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood). Kubrick uses elegant cinematography to show their mundane daily tasks, using a tracking shot to follow Frank as he circles around the exercise room of the space craft.

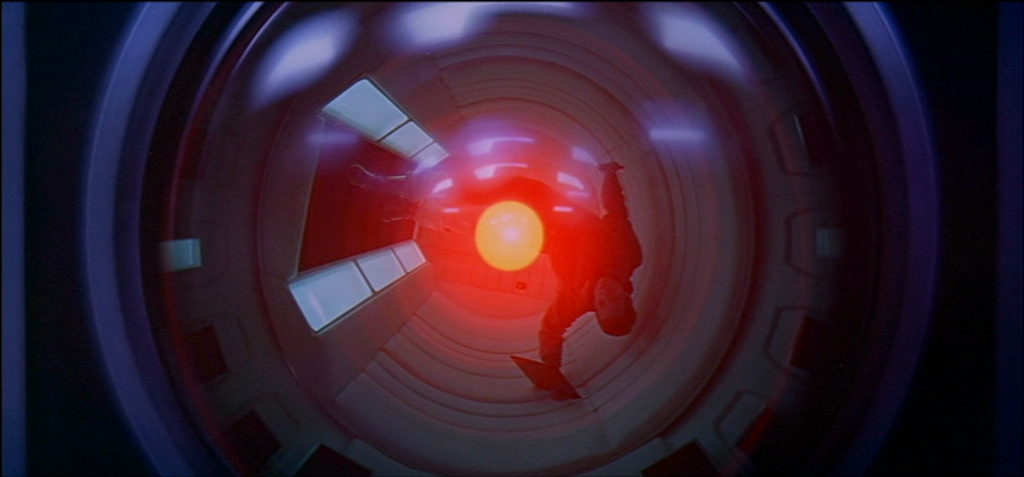

Helping steer their mission is the super-computer known as HAL 9000, an artificial intelligence entity who Kubrick characterizes with a monolith-like black rectangular panel, centered with a glowing red “eye”. He is voiced by Douglas Rain, and speaks in a manner that is uncannily warm, gentle, and seemingly empathetic. Kubrick ironically plays the men as robotic, emotionless humans who are so plugged into the mission and molded by boring routine that they only function as logical vessels. HAL exudes more personality than both men, creating conflict for the viewer when HAL starts to question the mission and his faith in its human crew.

The extreme-close up of HAL 9000’s eye is used to imply his thoughts through shot sequence

In one of his best moments of foreshadowing, avid chess player Kubrick shows HAL and Dave playing a game in which HAL bests the human counterpart, setting up a real game of chess the two would soon have. When HAL alerts the men a monitor outside the ship is do to fail, they retrieve it and look it over, evaluating it as fine. HAL defensively deems it “human error,” as his computer program record is flawless. The two men sense trouble brewing with the increasingly unstable HAL, and they decide to deactivate him while talking privately in a pod. HAL reads their lips and realizes his survival is at stake. All of Kubrick’s strength are on display in this tense part of the film, with composition perfectly framed, shots edited to imply precise meaning, and point of view switched to HAL at the last second, acting as cliffhanger before the film’s intermission. Kubrick’s use of the Kuleshov effect in this sequence, emphasizing the extreme close-up of HAL and the subjective meaning the scene has for the super computer about to commit atrocities.

Kubrick returns the audience from the intermission with the chess match between Hal and Dave beginning. In a sudden and shocking revelation to the audience, Frank is flung life-less into space. The robotic, calm Dave hurries to retrieve his body, and Kubrick takes his time with this sequence. The tension rises between Dave and Hal, as they battle wits to destroy each other to survive. Dave eventually de-programs HAL, and he begs for his life with more human emotion than Frank or Dave. Kubrick highlights the scene with his visuals, the sound effect of Dave’s breathing, and HAL’s dialogue.

Dave then follows a monolith into the Star-Gate. In a sequence that can only be seen and hardly described, Dave sees images of the known and unknown universe flash before him, a subjective view the the clinical Kubrick had held back until this fourth sequence.

After minutes of pure imagery and experience for Dave and audience alike, he finds himself in a neoclassical room as he views a man who looks like him eat at a table and eventually lay in a bed, with an aged appearance. The final monolith appears at the foot of the bed, and Dave is reborn as the “Star-Child” which overlooks the Earth at the films end.

In a rare moment of personal exposition, Kubrick explained his goals with the ending of 2001. Notoriously “Show/Don’t Tell” about his films, Kubrick allowed in this phone conversation a brief glimpse into his interpretations of the “diety beings” lodging Dave in a neoclassical “zoo” before morphing him into the “Star-Child.”

2001: A Space Odyssey is perhaps Kubrick’s most defined and awe-inspring work. By working with a script that lacked narrative clarity and emphasized cinematic experience, he crafted a film that perfected every form and technique that was lauded in the 20th century and pushed the envelope on what films could become headed into a new era of technology. The special effect shots are expertly crafted and hold up 50 years later, paving the way for an entire genre of philosophical, introspective science fiction films to follow. Kubrick’s use of classical music paired with carefully composed images would change film in a way that would have a lasting impact, and it would not be the final time he would apply the technique. Continuing his method of working with, but radically revising, existing source material, Kubrick reached the apex of his auteurship with 2001; ironically, Clarke would compose a novel based less on his own story than on Kubrick’s film. In essence, Kubrick’s vision ultimately eclipsed that of Clarke’s original short story.

Thematically, this film is Kubrick at his most reflective on human nature, how humanity uses tools for evolutionary advancement but also in deadly and dangerous ways, not too different from his critique of masculinity, warmongering, and violence in Dr. Strangelove. The search for other intelligent life and the origins of its creation also drive much of 2001‘s philosophical curiosity just as do the advent of machines and artificial intelligence. As mankind evolves, will it inevitably find itself doomed, unfit for survival? Examining evil in the heart of mankind would also bring Kubrick to the source of his next film, 1971’s A Clockwork Orange.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

During the late 1960s, Terry Southern loaned Stanley Kubrick the Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange. After reading it twice, Kubrick was engaged by the rawness of its characters and themes, deciding to pursue an adaptation with Warner Bros. at the expense of his never-realized Napoleon film. The appeal of the novel to Kubrick is apparent, with the main character Alex DeLarge expressing a taste for the theatrical and a lust for sex and ultra-violence.

Kubrick himself would of course adapt the screenplay, but he described the filming process as organic and playful with his cast of actors. Shooting entirely in England, he would cast many lesser-known actors of stage and TV on the UK circuit, highlighted by the importance of Malcolm McDowell, whom Kubrick admired as a charismatic rogue in Lindsay Anderson’s If …, as lead droog Alex. Long rehearsals would allow McDowell and other actors to ad-lib and improve lines in a natural environment, and Kubrick would change the screenplay before shooting would take place. His high ratio of takes would of course allow him the camera angles, movements, and flexibility in the editing room to craft scenes how he saw fit. The film is highly subjective, by Kubrick’s standards, grabbing the viewer’s attention from the opening shot and its voice-over provided by Alex.

Kubrick’s patented close-up of the face opens the film from Alex’s (Malcolm McDowell) point-of-view

A backwards dolly and zoom reveals the futuristic/expressionist mise-en-scene of the world Alex occupies

Kubrick frames the narrative into three separate segments, simplified as Alex pre-jail, in jail, and post-jail. The first segment shows Alex’s propensity for chaos and violence, as he views himself as a performer in a world that is his playground. He and his droogs, dressed in their absurd uniforms, travel the night looking for old hobos to intimidate, rival gangs to tussle with, and countryside homes to invade. Whatever their impulses guide them (and mainly Alex) to do, they act on. Kubrick presents this subjective worldview of Alex with some of his most stylish flair and craft. Wide-angle lenses on hand-held cameras capture the chaos of violence and rape on the ground level, intercut with extreme long shots and takes that are bombasted with quick montage cutting.

Kubrick stages the fight between Alex and his droogs against Billy Boy and his gang in an old abandoned casino, and set to the beats of classical music track “The Thieving Magpie.”

He displays the expression of violence that Alex enjoys as stylishly as possible, with high-contrast cinematography and lighting establishing that it is the ingrained nature inside humanity and Alex that he does not repress. Soon after, Alex and his droogs enter the home of a writer and his wife in the country side, immobilizing the man while Alex begins his ritualistic foreplay and rape of his wife. McDowell ad-libbed the inclusion of “Singin’ in the Rain” and Kubrick agreed that the irony of cheerful song during a terrible act highlights Alex disconnect from reality and submersion in pyschopathic fantasy.

Alex puts on a show as he acts out his rape fantasy

Kubrick ends Alex’s terror filled night with more irony, showing him returning home to his middle-class family flat. While putting away stolen loot underneath his bed, he plays with his snake (which is shot against a painting of sexual art) and prepares to listen to Ludwig van Beethoven, his favorite cultural activity. His arousal can not be contained at the sound of the music, which Kubrick accompanies behind a close-up of Alex while masturbating and viewing images of himself as a vampire, people being hanged/killed, and the crucifixion of Christ.

The Kuleshov effect from this quickly edited montage drives home the theme that sex/violence are intermixed with him as his free will is unleashed on the world. Kubrick uses quickly inserted shots and close-ups of Beethoven and other images in Alex’s head to give the viewer a subjective experience of his mentality.

A Clockwork Orange brings into question authority and free will in its second and third acts. After invading the home of a cat lady, Alex finds himself pitted against her in a game of “art as violence”, as she tries to fight him off with a bust of Beethoven (Kubrick has this satire stuff down!) as Alex attacks her with a giant’s porcelain penis, killing her with a blow to her head, and his droogs betray and leave him at the scene. After sentenced to 14 years in prison, Alex leads a very strict and totalitarian lifestyle. He finds escape only in the Bible, where violence and lust appeal to his nature. Wanting escape and salvation, he volunteers for the Ludovico treatment the British government is experimenting with.

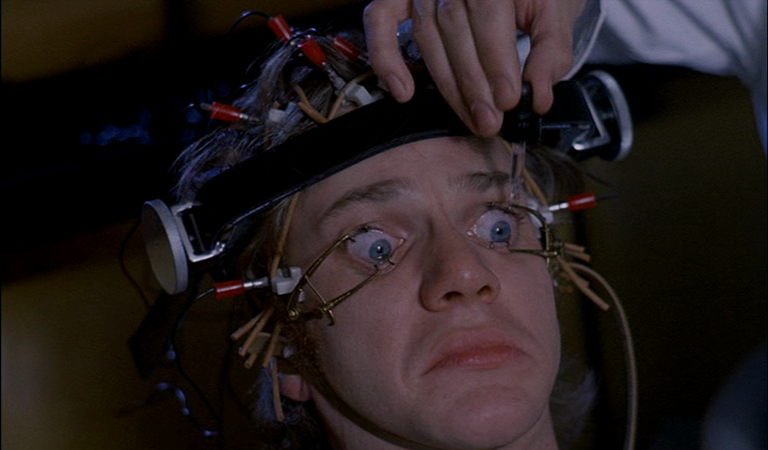

Alex being conditioned with the Ludovico treatment to repel his natural urges with the power of film

Extreme sacrifices are made on Alex’s part. The films he watches all contain sex and violence, which he will soon be repulsed by (effects of the drugs injected in him) and even his beloved Beethoven would no longer be a source of pleasure for him. Upon his release he is rejected at home by his parents. A series of coincidences and tragic ironies find him shortly after, with sequences mirroring the first act of the film. The old hobo recognizes him and chases him away. His old pals the droogs are now the police, and they drag him out into the woods for a terror-filled drowning–a baptism of sorts–that nearly kills him.

Even his former friends as corrupt policemen seek revenge on Alex

This scene reflects on the prior one of Alex enforcing his authority over Dim and George, but forcing them into the lake and Alex cutting Dim;s wrist as a final act of intimidation; Kubrick enhances the scene with slow-mo and classical music cut to the beats.

How Kubrick is able to convert Alex into the victim in the second half of the film shows his skill as a storyteller and filmmaker. Soon after his encounter with Dim and George, he by chance enters the house he once terrorized a man and his wife previously. This time, the man doesn’t recognize him sans mask, and gifts him hospitality and comfort as the “poor boy” who was victimized by the state with the Ludovico treatment. It is after Alex’s rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain” during a bath that the correlation hits him, and he conjures a sadistic plan of his own for revenge. In a backwards-dolly long take yet again (Kubrick repeats the motif in the film numerous times), the wheelchair-bound writer blares Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to the heavens, driving Alex mad as he leaps out the window hopeful of death.

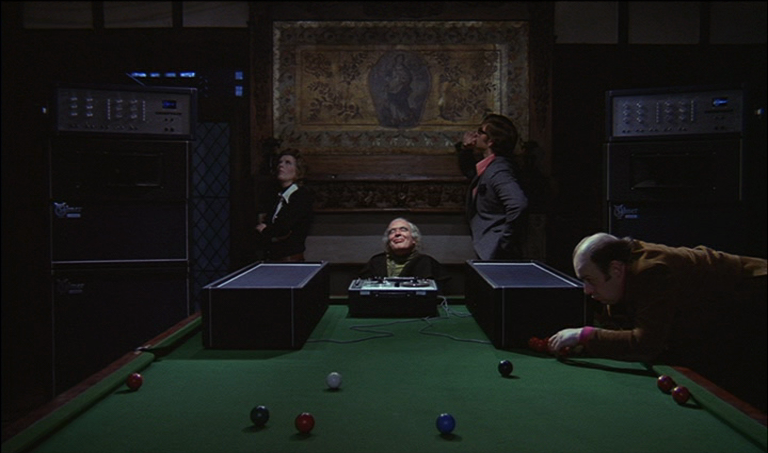

Mr. Alexander (Patrick Magee) takes great pleasure in torturing Alex with his beloved Beethoven

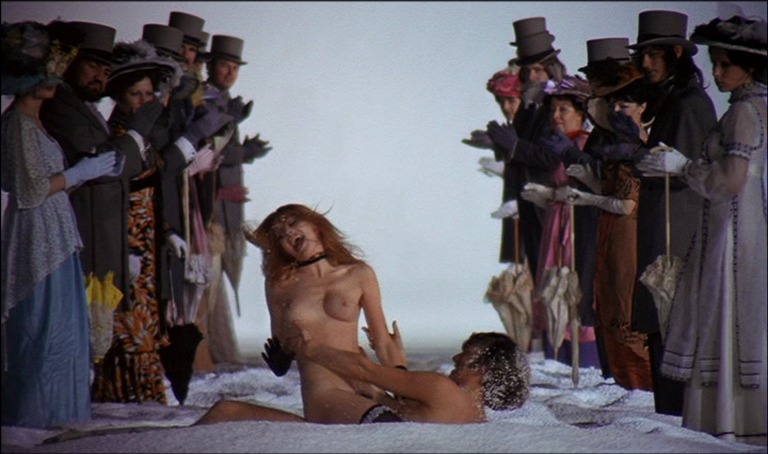

Kubrick finishes the film with the redemption of Alex, who despite all his evil deeds in the 1st act of the film, is allowed by Kubrick to have his “free will” granted back to him. Alex is hospitalized and the Ministry’s use of the Ludovico treatment on him highly scrutinized. The process is reversed and he is allowed his free will again. In the final moments of the film, he envisions sexual acrobatics with a young lady as Victorian folks cheer on. “I was cured, all right!”

Alex is once again free to think and act on his deviant impulses, with approval from society

There are very few filmmakers who could have made A Clockwork Orange as raw and unapologetic a film as Stanley Kubrick did in the early 1970s. Few auteurs had the confidence to risk pushing the envelope on such divisive themes or portray a subjective, often sympathetic, view of an anti-hero as twisted as Alex DeLarge. Kubrick had received some criticism for not pushing Lolita far enough a decade prior, and he also took heat from the U.K. public for taking his new film too far. After receiving death threats and hat email, he pulled the filmed from all U.K. cinemas until after his death, a sign of a man obsessed with the control of his artistic vision. His ability to take an original story, and create his own vision on screen was what separated from him for his peers at the time, having seemingly no equal in the American Hollywood system,

Critics were split at the time, still uneasy about the graphic content of the film, but upon reflection A Clockwork Orange has been regarded as a masterwork by a bold and ambitious auteur. When presenting violence and sex on screen with his characteristic long takes, tracking shots, montages, slow-motion, time lapse fast-motion, and exact cutting to classical music, Kubrick was at this time a master of his tools to tell a story and elicit a response from his audience.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks