Waiting for test results is never fun, but what makes test results most anxiety-inducing is if the results are for something significant, such as a final exam or a test result for COVID-19. It’s hard not to spend your time obsessing over the “what if’s” and convince yourself it’s all over while waiting. In the 1962 film, Cléo from 5 to 7, Agnès Varda directs her rendition of what it feels like to wait for a test result. Through the character of Florence, or Cléo, played by Corinne Marchand, she experiences the ups and downs of waiting two hours, but finds relief in someone who she never thought she would.

Some of the French New Wave films we have already covered in Issue 1 and Issue 2 depict political messages about wars or past wars, and this film follows suit. While it isn’t as direct as Masculin Feminin or Hiroshima Mon Amour, the movie came out very shortly after the Algerian War of Independence. To be precise, about a month after the war ended. Since the whole film was shot in Paris, everything you see on the streets was real. When Cléo and her maid Angèle (Dominique Davray) are riding a in a taxi to get home, the radio talks of riots and the war in Algeria. Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller), the male companion she meets towards the end, is on leave from fighting in Algeria and is against the war himself as well, claiming “people are dying for nothing” (Cléo from 5 to 7).

The subtitles of the radio while driving.

Similar to Purple Noon, you can see passersby taking a long look directly into the camera as Cléo walks down the street, many of which being elders and there are many point-of-view shots in the film from Cléo, which makes the direct stares more intimidating. What I first thought when I saw them look into the camera was an emphasis on getting older. Cléo is distraught by her uncertainty of the test results, and it is made clear that she believes her beauty is the only thing she has left, making her very vain. For instance, when she looks into a mirror, she says to herself, “Wait pretty butterfly, ugliness is a kind of death. As long as I’m beautiful, I’m even more alive than the others”. Another example is when she goes shopping for hats with Angèle. Cléo carelessly tosses the hats around while she tries them on and in the mirror says, “Everything suits me. Trying things on intoxicates me!” Thus, I thought the staring was due to Cléo worrying about getting older and losing her delicate features, but now I know it was due to being shot on location. Either way, the duality leaves it up to the viewer to decipher deeper meaning within the scenes.

One lady who is looks directly at the camera.

Another lady who is looks directly at the camera.

A couple of ladies who look directly at the camera.

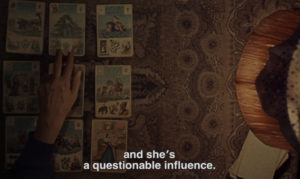

The beginning of the film starts in color, which surprised me since I thought it would be in black and white due to the thumbnails on The Criterion Channel, where I watch most of the films. While the film did start in color, it would flash between color and black and white. The perspective we are shown is an aerial shot of a table with the tarot cards. We are also presumably positioned from the tarot reader’s perspective since we are viewing the cards from her side. When Cléo is shown, it is in black and white, and the rest of the film after the tarot card reading scene is played in black and white. I think this implies that Cléo only sees things in black and white. As she is overthinking what is to become of her, she only sees yes and no, right or wrong, and life or death. There are no in-betweens for her, which is why she acts so dramatically.

The aerial perspective from the Tarot reader in color.

A shot of Cléo (Corinne Marchand) in black and white while she talks to the tarot card reader.

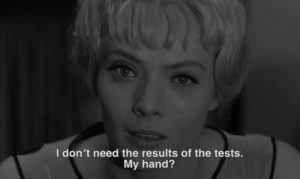

About halfway into the film, Cléo’s friends, who are also her songwriters, Bob (Michel Legrand) and Maurice (Serge Korber), come to show her some new songs they are working on but as she sings, she breaks the fourth wall and looks directly into the camera as the melancholy lyrics start to match up with her own life and fears. Tears begin to stream down her face, and she breaks down. She states that everybody spoils her, but nobody loves her. The ones around her who are supposed to care about her tell her she is overdramatic and she should calm down. Later, she meets up with a friend named Dorothée (Dorothée Blanck) and Cléo tells her about her illness. Her friend seems to be more genuine in her concern but still tells her the same thing: she might be over worrying.

Dorothée’s husband works at a movie theater and they stop by to say hello and watch a short film. The short —lasting about three minutes— is shown like we are watching the movie on its own. The plot is about a man saying goodbye to his girlfriend dressed in all white as she walks down the stairs. He puts sunglasses on, and he sees another version of the girl, only this time she is dressed in all black. The girl in all black gets sprayed with a water hose, and by chance, a hearse comes by and picks her up, thinking she is dead. The man is too slow to catch up with the hearse, and he takes off his sunglasses to wipe his tears away. He then sees his girlfriend in all white again, exactly where she was waving goodbye to him. The same thing happens to the girl in white, only this time with a sailor, a rope, and an ambulance. Luckily, he is able to stop the ambulance, and they rejoice as they embrace each other. I thought it was strange to have this short film interrupt the narrative, but then I realized that it’s another way of looking at Cléo’s situation. The sunglasses are like Cléo’s fear; everything seems dark and gloomy when she is wearing them. If she were to take them off, she would realize she is worried about something that she can’t control. Yet, she doesn’t know she is still wearing the sunglasses. To her and Dorothée, the film is found funny and carefree. Again, her friend does not take her seriously, just like Angèle, Bob, and Maurice.

The girl in all white saying goodbye.

The girl in all black saying goodbye.

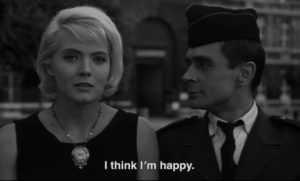

By the end of the film, she meets Antoine, and he agrees to go to the hospital with her if she goes to say goodbye to him at the train station, while they travel to the hospital here is an extended scene where they are riding the bus and making small talk. Although Antoine talks about positive things and Cléo counters them with negative things, it seems to keep her mind off of the impending doom she has been feeling over the last two hours. When they arrive at the hospital, she gets her test results from the doctor, and he says she will be fully cured of her cancer with two months of chemotherapy. Finally, Cléo says to Antoine, “I think my fear is gone. I think I’m happy”, and Cléo is happy. They walk down the long pathway together as she smiles like she means it for the first time in two hours.

Cléo is finally happy.

Cléo finally smiles with Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller).

While the film portrays only two hours of Cléo’s life, it feels more like an entire day because of everything she sees and does all wrapped up in her anxious state of mind. Her close friends did not help her calm her nerves. Being the last person she expected to meet, Antoine was able to calm her fears by just talking to her and keeping conversations positive. That is the film’s theme: to stay positive and be there for your loved ones when things get tough. Although Cléo’s test results weren’t fatal, the film tells us that we should never assume that someone is overreacting. Their problem might seem small to us, but to them, it could mean more than life. The French New Wave was mainly composed of male directors and Varda was one of the very few who were recognized among the big dogs. Cléo from 5 to 7 is the first Varda film out of three that I analyze on our journey through French New Wave film, and I’m very excited to see what’s in store for us based on just this one masterfully done film.

Recent Comments