Trigger warning: Before I begin, I want to mention that this essay involves discussion on suicide, depression, and contains images depicting both, as the film’s message and plot centers around these topics. If you or a loved one are dealing with harmful thoughts, please read at your own risk, and seek help if needed. National Suicide Hotline: 800-273-8255.

Everybody has their bad days. It’s the small, minor inconveniences throughout the day that add up to make it seem like a little rain cloud is hanging above your head and following you wherever you go. Sometimes, the rain cloud never leaves. Le Fou Follet, or The Fire Within in English, is a 1963 film directed by Louis Malle and follows a writer who has overcome his alcoholism with rehabilitation, however, he still suffers greatly from depression and anxiety. He decides to take his own life, but visits some friends in Paris before he does.

Louis Malle never shied away from emotion and realism in his films, but this one was by far his most intimate. Le Feu Follet was inspired by the book Will O’ the Wisp, written by Pierre Drieu La Rochelle in 1931. The book tells a story very similar to Malle’s screenplay, but instead of alcoholism, it was a heroin addiction. Malle also used Jacques Rigaut as his muse for the character of Alain Leroy (Maurice Ronet). Rigaut was a famous French poet who was part of the Dadaist movement and frequently wrote about suicide in his work. On November 9, 1929—the suicide date he made public— Rigaut had shot himself in the heart. He died at only 30 years old.

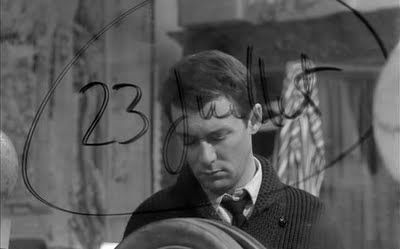

In the screenplay, Alain uses a gun to shoot himself in the heart while using his fingers to make sure the blow will be fatal, as well as a date written on his mirror in whiteboard marker, which was presumably his planned suicide date, similar to how Rigaut used a ruler and had a public suicide date. Since Malle wrote and directed the film, he must have gone through similar feelings for the film to be so simultaneously raw, beautiful, and tragic. No worries necessary about Malle though – Malle lived to be 63 years old and knowingly died due to lymphoma in the comfort of his own home.

French New Wave films don’t hold back on showing human venerability, and death is seen in almost every film in some shape or form, although, when the whole story is based around the idea of wanting to die, the actors simply can’t go lay down on the street or scream at the top of their lungs. There needs to be passion and commitment, that’s why Ronet’s acting in the movie is beyond brilliant. He had the perfect look for the film too. Suppose you’ve seen the 1996 crime thriller Fargo with Steve Buscemi. In that case, the characters make light fun of Buscemi, calling him ‘funny looking.’ Comparing that to Ronet’s role, other characters throughout the film continuously talk about his physical appearance and how he looks sad and worn down, which Ronet does. In my opinion, he fits the role perfectly in every single way.

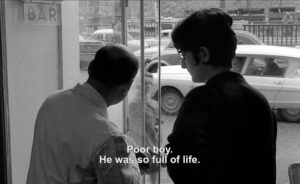

His old friend Charlie (René Dupuis) and a hotel assistant talk about Alain after he leaves.

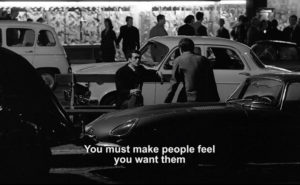

Eva (Jeanne Moreau) talks about Alain directly to him.

Comparatively to Cléo from 5 to 7 and Shoot the Piano Player, all three characters—Cléo, Charlie, and Alain—have existential dilemmas but each character finds a different way of dealing with existential dread. With three different ways of looking at the same question—to live or to die?— each film puts into perspective how diverse life is and how everybody has their particular problems that need to be treated differently.

The streets and housing in Paris are similar to a labyrinth and are set up very differently from houses and buildings in the U.S. Since many of the shots are long takes and show only a fraction of the environment, it seems like Alain navigates through a maze at times. For example, while he and Eva walk back to Eva’s house, they go into a courtyard. You’d think that the house would stem from one of the many doors, but instead, they go into a side garden. Then, they keep walking and take another turn, which leads them into another courtyard where their front door is. Even the inside of Eva’s house is a maze. Eva’s artwork is strewn throughout the house, and there are columns and half walls that create interestingly spaced out rooms. One room is entirely covered in rugs, tapestries, and full of couches adorned with big pillows and blankets. The camera has to work around the environment while Alain paces through the objects. The confusing layout contributes to being shot on location. As seen in Purple Noon and Cléo from 5 to 7, some of the shots show people staring directly into the camera as Alain walks down the streets of Paris. You can even see the camera’s reflection in some of the windows he passes by.

Here, the screen may look split, but it’s due to the dividers and layout of the room.

Le Fou Follet gives us some background info on Alain before he visits his friends. He stays at a rehabilitation center even though he is cured of his alcoholism. He doesn’t leave because he is afraid to face society again. Alain seems troubled, yet has accepted the life he is living— as if there was nothing he could do to change his own mind. He spends his days in his room looking out of the window and reading a book. Sometimes he will wander around thinking or reminiscing about his younger years. From the very beginning, we know Alain’s life was exhilarating before he went to rehab. All the friends he goes to meet are in their middle-aged years, and they all have some sort of funny memory with Alain due to his drinking.

When his planned suicide date comes, he travels to Paris to say goodbye to his friends and possibly find one last reason to live and his friends are compassionate and genuine, and many of them invite him to live with them. It’s clear they truly care for him, yet they don’t exactly see what Alain sees. They try to help him by explaining what makes their lives enjoyable, but that is the problem – Alain tries to explain himself, but his friends keep repeating the same things that make them happy, or accept that Alain is too far gone. It’s an endless cycle. Close to the end of the film, he relapses and gets drunk at his friend’s dinner party. He finally breaks down and starts to explain that he cannot “touch anything,” even if he wants to. While Alain paces back and forth, the film cuts more rapidly as he becomes more agitated to show precisely how he feels. He leaves with an acquaintance from the party (Bernard Tiphaine), and they have a deep conversation as to why Alain feels the way he does. The conversation offers no consolation to Alain, but we finally get to see him open up about his feelings. Not to mention, they are in the most beautiful city in the world. If I lived in Paris, i would walk around the city every night with all the glimmering lights and old stone streets.

Alain and his friend (Bernard Tiphaine) talk in the street.

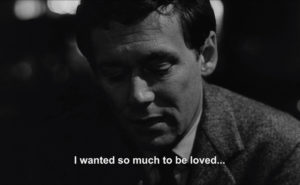

A part where Alain talks about why he loves.

Alain might have been looking for something he would never find if he had already made his mind up about dying. He was missing the element of wanting to get better. It doesn’t matter how long the healing takes or how you recover—in healthy ways—as long as the want is there. Thus, the message from the film is entirely subjective. I can’t tell you that this is the only way depression feels—and I’m certainly not qualified to— because the feeling differs for everybody. However, I am confident that Malle was trying to communicate that you cannot find happiness in other people. Friends and family are great for support and needed in recovery, but they are never the answer for your own happiness. French New Wave directors must have had a bigger grasp on life because its mind-blowing knowing that human emotions like depression and sadness that can be so prominent in life, people such as Malle, Truffaut, or Varda can create a whole film based on just that feeling and have it be so accurately represented.

Recent Comments