Full Metal Jacket (1987)

By the mid-1980s, Kubrick and screenwriter Michael Herr had become fascinated with Gustav Hasford’s novel The Short-Timers, a depiction of the Vietnam War through the perspective of a Marine trained to kill. War had been an obsession of Kubrick throughout his career, his having been drawn to examine man’s allure to violence in Paths of Glory, Spartacus, Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, and The Shining. As in his previous adaptations, Kubrick would work in a recognizable genre–here, the “war film”–but bring his own creative style and leave a lasting influence for others to follow.

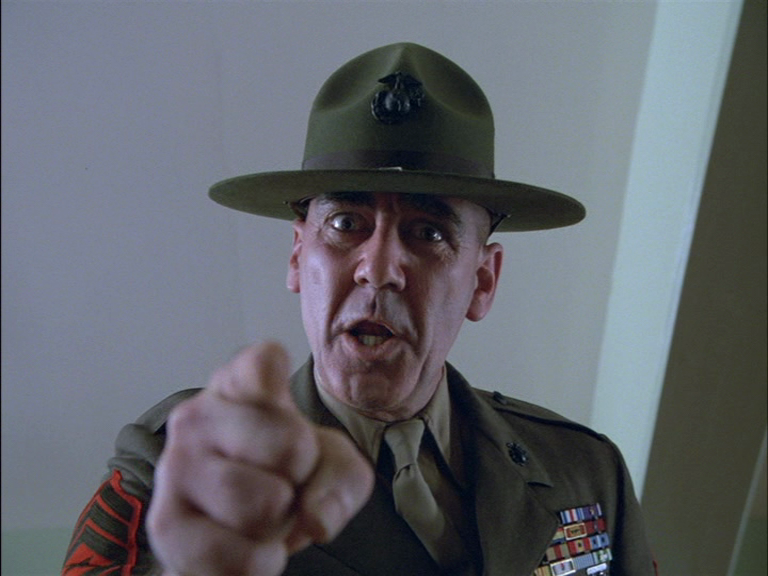

Full Metal Jacket would be adapted from The Short-Timers and released in 1987. The story centers on Pvt. Joker (Matthew Modine), who gives occasional informational and sometimes ironic first person narrative. Continuing to create non-traditional narrative convention, Kubrick splits the narrative into two parts: Jokers time at Parris Island, SC training to become a Marine and then his deployment to Vietnam for the war. The first half shows the mental and physical tax it takes to become a Marine, “trained to kill” by the verbally and physically abusive Drill Instructor Sgt. Hartman (R. Lee Ermey). Ermey would end up being a valued asset to Kubrick in production, first cast as a “consultant,” but soon, as Kubrick noticed, simply too good not to have the part. At least half his dialogue was improvised.

Kubrick uses a low-angle medium close-up of Sgt. Hartman (R.Lee Ermey) to give the audience a subjective view at boot camp

Pvt. Joker is named as such for his rebellious and sarcastic nature, traits that would be paramount for Kubrick as he places the military journalist into warfare in part two as both war critic and ground fighter. Joker befriends Texan recruit Pvt. Cowboy (Arliss Howard) who he would meet up with again in Vietnam, and is tasked with helping the incompetent Pvt. Pyle (Vincent D’Onorfio).

Pvt. Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio) wears the “Kubrick stare”, a signature for human madness seen in his films

The first section of the film comes to a cold and brutal end, when Pvt. Pyles descent into madness erupts in murder suicide. Despite Joker’s best efforts to de-escalate, Pyle uses live ammunition to shoot Sgt. Hartman and then turn the gun on himself.

Chilling blue lighting highlights the abuse of Pvt. Pyle as his training to become a “killer” goes horribly wrong

This scene echoes the mise-en-scene of the early scene where the recruits mercilessly beat Pvt. Pyle with soap wrapped in towels. A steely blue light pierces both scenes and Kubrick’s daughter Vivian Kubrick’s seething synthesizer score chills the bone. Not unlike his ellipses in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick jumps ahead to Joker already in Vietnam for some time, imminently ready to leap “into the shit.”

Dressed with a peace sign clipped to his jacket and a “Born to Kill” slogan on his helmet, Kubrick uses Joker as walking contradiction and critic of the war from the American perspective, complete with authority figures questioning his motives.

Joker represents for Kubrick the duality of man, both questioning the motives of war and participating in it

Much like Paths of Glory, Kubrick is more interested in the “grunt” perspective than the politics of war, and depicts the style of war as ugly, grim, and hyper realistic. Sets and locations are littered with broken buildings, fallen concrete, fire, and smoke. He veers from his style of classical music as background score, instead opting for ironic contemporary uses of “Hello Vietnam“, “These Boots are Made for Walkin“, “Surfin’ Bird“, and “Paint it Black.”

One of the most self-reflexive ideas Kubrick uses in the film is his use of the documentary film crew filming Joker/Cowboys squad as they enter Hue City among enemy combatants. Long take tracking shots capture the film crew at work, contrasted by deliberately satirical interviews of the marines who can barely articulate why they are fighting in Vietnam, speaking in cliches and blood thirst.

Joker can always be counted on to make a mockery of the Marine consensus for killing. It is in the final act of the film when the squad faces off with a young Vietnamese female sniper that Kubrick pulls out his bag of technical tricks. Deep-focus cinematography, zooms from the killers POV (seen below), and slow-motion shooting show the hyper-realism style of warfare he prefers to displays.

Full Metal Jacket was lauded as being one of Kubrick’s best and most faithful adaptations. While some could argue over authorship of the story between he and Hasford, Kubrick no doubt has ownership over the story as told on film. Kubrick omitted some of the most brutal atrocities in the book, particularly explict sexual and violent matters committed by American soldiers. Kubrick was aiming to say less about the extreme actions of war, and instead focus on the natural urges in main for lust and bloodshed. The attack at Parris Island by Sgt. Hartman on his Marine recruits aims to emasculate and humiliate them into killing machines.

Kubrick’s signature use of perfect symmetrical compostion

Kubrick has examined this in most of his filmography, but never in such a cause/effect matter in this dual narrative. The helicopter gun man shoots down the Vietnamese without discretion, a product of Marine training conditioning. The only escape Marine men have from their homosocial circle is the bargaining for sexual encounters with Vietnamese prostitutes, recalling Kubrick’s exploits of men’s obsession with sex and destruction in Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange. The young men of Full Metal Jacket, led by their desires and training can only sing-song the nostalgic tune of Mickey Mouse as they march through destroyed cities at film’s end.

There is prevailing thought that connected to the auteur theory is the notion that filmmakers spend a career remaking the same film again and again. While I think this could appear true on the surface, we see Kubrick repeat a pattern of adaptation with idiosyncratic style. His technical proficiency was well established in the 1960s, and he would frequently choose narrative material that examined the themes he would want to explore and dissect. He would eventually hit an apex that made it known when you were seeing and experiencing a Kubrick film as if you were reading a novel by Faulkner or Hemingway. Kubrick was finishing his career on a high note still creating films in his singular vision style, a career that would finish strong in the 1990s with his final piece of work Eye Wide Shut.

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

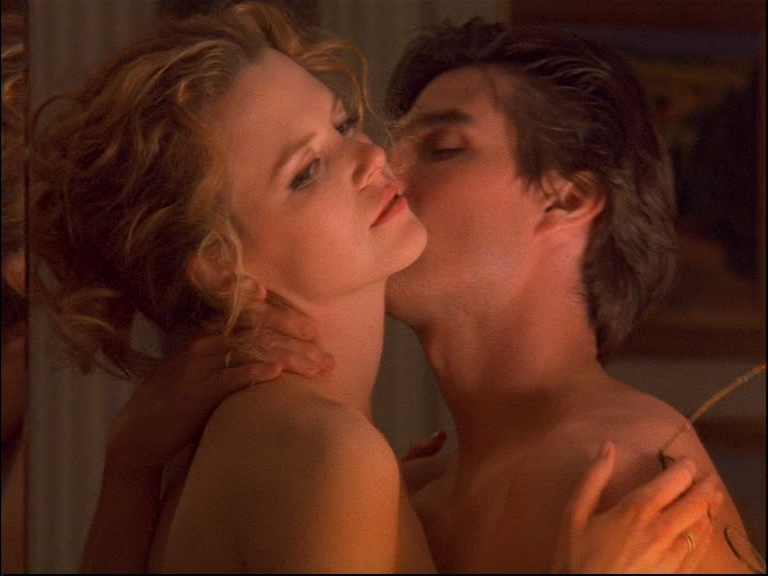

It seems fitting Eyes Wide Shut would be his final film, as throughout Kubrick’s career he often dissected the flaws and faults at the human heart, examining how those insecurities came to the surface in the form of violence, death, love, and sex. He had been enamored with the 1926 Arthur Schintzler novella for decades, and finally adapted a screenplay to his liking in the mid-1990s. With the help of Frederic Raphael, Kubrick changed the setting of 1920s Vienna to modern-day New York City. At the center of his erotic drama he cast Hollywood super-couple Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as Dr. Bill and Alice Hartford in a story of jealousy, mystery, and sex.

Kubrick subverts the notion of “Hollywood’s Sweethearts” with the casting of Tom Cruise & Nicole Kidman in an erotic drama

Even in his seventies and near death, Kubrick was methodical and controlling with every aspect of the production. Shooting in England like usual (he had a fear of flying), he used sets and locations to re-create the street level Manhattan setting and with cinematographer Larry Smith he emphasized color and decor in the mise-en-scene of each set and shot. Music composed by Jocelyn Pook provided a moody and dream-like atmosphere for the film.

Eyes Wide Shut introduces New York couple Bill and Alice Hartford, a well-to-do marriage that is supported by Bill’s job as a Doctor, and with their daughter they seemingly have the American Dream. When they attend a party hosted by rich socialite Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack), both Bill and Alice face temptation for infidelity. Bill is courted by two young and attractive party guests before he is summoned to revive a drug overdosed prostitute in Zieglers private quarters. Alice is shown dancing with a over zealous, rich Hungarian man (Sky du Mont). Later that night after having sex and smoking pot, the too get into a debate on who the two sexes differ in sexual philosophy and Alice aggressively tells Bill the story of a Naval office she would have slept with the summer prior if given the chance. Disturbed by this revelation Bill goes out into the night looking for sexual satisfaction for his bruised ego.

Bill’s (Tom Cruise) jealousy and insecurity would set the tempo for a strange night ahead

In the night, Bill encounters the daughter of a recently deceased patient who comes onto him, a “heart-of-gold” prostitute named Domino (Vinessa Shaw) he nearly sleeps with before being interrupted, and attends a costumed party at a nearby rural mansion.

While at the party hosted by a secret society of social elites, he witnesses the rituals and sexual fantasies played out in an ongoing orgy before he is sought out by the group as an outsider. Warning him of grave consequences, he leaves, and the third act of the film echoes what came before it as Bill deals with the shame and danger of the near infidelity he committed against his marriage the night before.

Kubrick’s perfectionism is on full display in Eyes Wide Shut both as an auteur and a technician. His long-take aesthetic gives the film an immersive and near dream like quality. Steadicam and wide-angle lenses (a long-time Kubrick staple) give him the freedom for a spatial and temporal depth of field unlike other films makers. In this clip below Bill is brought forward to be judged for his intrusion. Kubrick uses subjective camera view and long take tracking shots to highlight Bill’s anxiety and isolation.

Use of dissolves carry viewers from room to room throughout the mansion, a form of editing not typically used by Kubrick His subjective use of cinematic language takes effect when Bill imagines the graphic nature of his wife cheating on him with a Naval officer, which Kubrick shoots in a stark fashion and using his Kuleshov effect he inserts it into the narrative five times, putting the viewers into Bill’s fragile psyche each time.

Bill fantasizes about Alice’s confession, leading him to imagine the worst

The majority of the film comes from the limited point of view of Bill, who travels as an outsider to the mysterious mansion and he acts as voyeur and trespasser among those he thinks he belongs to (he shows his business card as a doctor, thinking it gains him access into higher society). The third act of the film feels to the viewer like the morning after a dream or nightmare, as Bill attempts to piece together the reality and consequences of the night before. Because Kubrick limits the narrative knowledge of his protagonist, all questions cannot be answered, and he uses the paranoia and confusion of Bill to his cathartic advantage.

Cool blue lighting and perfect composition reveal Bill’s costume mask as a chilling memory of his actions

Eyes Wide Shut would be a fitting capstone to Kubrick[s career and life. He died four days after delivering “final cut” to the studio, but there are those who question if the film was completed to his full satisfaction. Like most Kubrick films, it garnered divisive reviews upon release (film maker Martin Scorsese praised it as one of the best of the decade), but upon reflection has gained higher esteem. With Kubrick’s reputation for numerous takes while filming, the film also holds the record for longest film shoot at 15 months at the time of its inception.

Kubrick allows Bill and Alice a shot at redemption through forgiveness and reconciliation.

The film examines everything at the heart of Kubrick’s thematic turntable: the dark side of sexuality and human desire, how it conflicts with love and decent society, and how it can surface into bigger problems. Eventual problems of violence and death, consequences of love and sex and how that conflict for the human condition is a deep-seated issue for mankind. Stanley Kubrick lived and died to make technically impressive films, adapting existing narratives into his own cinematic visions, and using his own brand of cinematic language to engage audiences with his reflection of what he saw in each of us individually and as a whole.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks