Barry Lyndon (1975)

Looking for a new challenge after his most successful stretch of work, Stanley Kubrick turned to adapting the William Makepeace Thackeray 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. Funded by Warner Bros. for the second straight film, Kubrick would again have complete control as writer, producer, and director. An initial budget of $2 million ran up to $10 million, as Kubrick sought authenticity and perfection in costumes and set designs and innovated new techniques cinematography not seen before. The rise and fall of Barry Lyndon would be a three-hour long tragic tale about human greed and the failures of societal structure.

Kubrick would change the narrator from the novel from first-person perspective to third-person, his avenue to bridge cardinal functions of story in a more detached and objective manner. While Kubrick was lauded for his technical mastery, he also deserves credit for his work as screenwriter and adapter, as he had shown for twenty years the ability to take the plot of a narrative, and re-tell it in his own form of storytelling–the mark of a true cinematic auteur. In Barry Lyndon, Kubrick would use a unique two-act structure, symmetrically detailing the climbing of the social ladder by protagonist Redmond Barry (Ryan O’Neal) and subsequent fall from grace by his alter-ego Barry Lyndon. Young Irish lad Redmond Barry is forced into exile after injuring a British captain in a duel for the right to his cousin’s affection.

Kubrick captures a beautiful landscape shot as the duel decides Redmond’s (Ryan O’Neal) fate

After being robbed by a highwayman, Redmond has no other choice but to join the British Army as a soldier in the dangerous Seven Year War. He deserts and ends up in the Prussian Army, gaining favor with a captain who wishes to use him to spy on an unsuspecting gambler Chevalier (Patrick Magee). Barry takes sides with the fellow Irishman in disguise and escapes across Europe with him, cheating rich aristocrats out of fortunes in card games. Seeking wealth and nobility for himself, Barry sees an opportunity to win the love of Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson).

Kubrick directs his actors in an unconventionally subdued fashion

After the death of her ill husband Charles, Barry swoops in and marries her, to the objection of her ten year old son Lord Bullingdon. But upon having a child with her, Barry quickly spirals into infidelity and excessive spending on material objects. His rivalry with Lord Bullingdon (Leon Vitali) festers over the years, eventually leading to the young adult Bullingdon’s departure. After the tragic death of the Lyndons’ nine-year-old son Bryan, the two fall into isolation and despair. Lord Bullingdon returns to seek back the honor for his mother and the Lyndon estate in the form of a pistol duel.

A well framed shot of Lord Bullingdon (Leon Vitali) before he meets Barry in a pistol duel with honor at stake

The production of Barry Lyndon would undoubtedly be as realistic to the material as Kubrick could master. Authentic outfits of the time were used, and the inside of countryside manors remodeled to appear as realistic as possible. Kubrick was insistent on refusing to use artificial electric lighting when framing shots, instead relying heavily on sunlight through windows and, in particular, candlelight for interior shots.

Obsessive use of natural lighting created “painterly” cinematography in Barry Lyndon

Innovations with camera lenses and candlelight gave Barry Lyndon an unique look

Fields, farms, and manors close to his English countryside estate were used as locations. Kubrick used super-fast 50mm lenses he obtained from Zeiss that were used for the Apollo moon landings, gaining him a wide aperture and ability to capture more detail in a dimly lit room.

The usual stable of Kubrick cinematographic tricks would be applied to the visual storytelling of Barry Lyndon. Expanding upon his use of slow-dolly, slow-zoom shots going from close-up to long shots in A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick would use them extensively in Barry Lyndon. In the scene below, the technique is employed to depict the loneliness felt by the protagonist.

In this film the mise-en-scene is slowly developed from the use of slow dolly/zoom shots, and the zoom shots bring on a different connotation than seen prior in Kubrick’s work. Kubrick creates scenes of beautiful “moving pictures” in the sense of re-creating paintings of the time, but also exposing the stiff and superficial facade of eighteenth-century Europe.

Kubrick composes a shot of the desolate Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) and her son as an imitation of 18th-century portraiture.

Barry was an Irish man from a middle class upbringing, trying to find identity in a world that grants power only to the already powerful. Social mobility is non-existent in Barry’s world and his attempts at changing the fates only occur through lies and deceit. In an ironic twist on his narrative evolution from A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick crafts the story or Barry Lyndon in reverse order. Where Alex DeLarge falls from grace as psychopathic delinquent into victim of the state, robbed of free will (but eventually allowed to be himself again), Redmond Barry’s journey is positioned as one of survival and potential for happiness, fallen by the sins of Barry Lyndon who ends up with nothing. Conventions of melodrama lay framework for the second act of Barry Lyndon. Barry falls as husband, when he neglects his new wife Lady Lyndon, and constantly cheats on her with her handmaidens. This infidelity and greedy opportunism is realized by his stepson Lord Bullingdon, who despite constant whippings from Barry, never forgets the sins of his stepfather. Conversely, Barry spoils his son Bryan, who through mischievous disobedience, is thrown from his new horse and dies shortly after. The sins of Barry Lyndon catch up to him, dismantling the life he always tried to manifest but could never reach. Kubrick allows moments of sympathy for his title character in the climax of the film, when he mercifully loses a pistol duel to his nervous but determined stepson, and takes a $500 annuity to leave the Lyndon estate for good.

Barry Lyndon is Kubrick’s commentary on social structure in society and the inane systems used in all eras of history. Violence and death have a never-ending impact on Redmond Barry’s life, from the death of his father, destruction of war, death of Charles Lyndon, death of his son, and final duel with Lord Bullingdon all providing sharp edges to a life he could not shape. Barry Lyndon was one of Kubrick’s most lavish attempts at an “art” film, a feat he successfully crafted with aesthetic beauty and thematic heft.

Kubrick would have perfected his landscape shots since Spartacus and 2001: A Space Odyssey

Kubrick’s fondness of classical music as musical score would be appropriately applied to the film, with pieces by Bach, Vivaldi, Paisiello, Mozart, and Schubert creating immersive tone and atmosphere. The main theme would be repeated as leitmotif throughout and be associated as one of the iconic uses of classical music in his films. The Academy Award-winning cinematography of John Alcott would create some of the finest images of the 1970s. By this point in his career, Kubrick was a well-established auteur and cinematic storyteller. His ability to take pre-existing stories and adapt them into his world with technical prowess and narrative ingenuity would change cinema for those who followed him. Having established his signature style, competence in all aspects of production, and thematic repetition, Kubrick was making some of the most distinguished–and distinctive–films in the Western cinema.

The Shining (1980)

In the late 1970s, Kubrick gravitated towards an adaptation that would bring him closer to mainstream cinema. While his films had gained him respect among his peers, Kubrick wasn’t a household name with the general film public. By adapting the popular 1977 Stephen King horror novel The Shining, that would soon change. Kubrick would enlist the help of novelist Diane Johnson to co-write the adapted screenplay, and the two would make changes that would not sit well with the novel’s author. Kubrick was interested in the central story to The Shining, but had to make certain cuts and changes to fit his auteur’s vision of what the film adaptation would become. Of these, the casting of Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance was paramount.

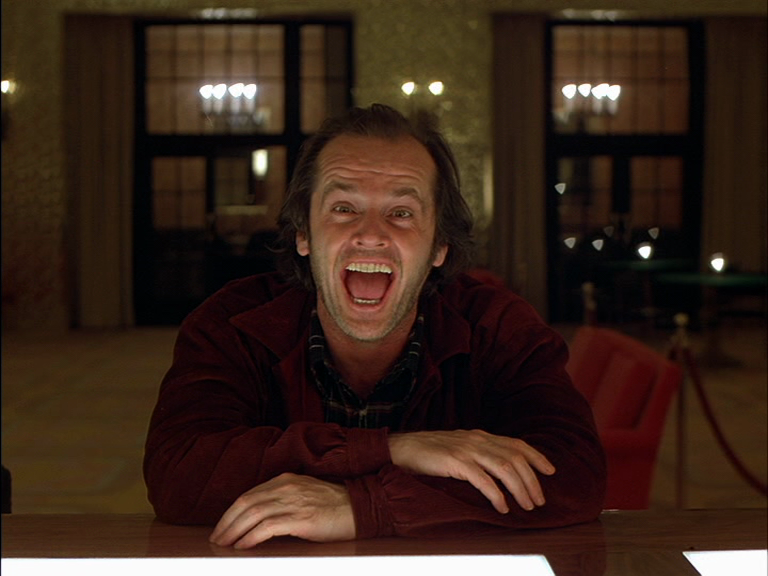

The eccentricities of Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance give The Shining a dynamic lead performance

The Shining is a horror movie in the general sense, with the spiritually enhanced Overlook Hotel setting up the Torrance family for a winter of isolation and freight, as ghostly spirits terrorize and influence them all in different ways. Jack Torrance, his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall), and son Danny (Danny Lloyd) set out to act as caretakers for the isolated hotel during the depths of the frozen Colorado winter. Cracks in the familial foundation are exposed early and often, and the mental breakdown of the patriarch Torrance drives the descent into narrative madness the entire family endures.

Mirrors and duality play a big role in the hotel as Jack descends into madness

Kubrick and Johnson read up on Freud’s writing of “The Uncanny”, and knew that they wanted to Overlook Hotel to reflect psychological horror deep within the mind. Just as he had previously mirrored societal fear and insecurity about the cold war and artificial intelligence, Kubrick was fascinated with the subconscious and how it could manifest into the world of those who become overcome by it. The film routinely shows visions, images, and manifestations the characters and audience can’t decipher as real or fantasy. Kubrick does not display his ghosts in a semi-transparent fashion, instead displaying actors as characters that seem normal to the Torrance family. He uses an eerie and innovative use of the Steadicam to track his characters for long and elaborate takes (inventor Garrett Brown was heavily involved with the production). This technique allows him to subject the viewer to the vast, maze-like layout of the hotel that enslaves the characters, as well as execute a a freeform subjective view of the composition. Kubrick establishes this visual motif from the very first scene, with a wide-angle lens from a helicopter following Jack Torrance as he snakes around the roads up the Rocky Mountains. Similar cinematography would follow each character through the hotel and maze, similar labyrinths on the same foundational grounds.

By now a complete master of mise-en-scene, Kubrick methodically plans and executes every shot of The Shining, including the music. Using non-traditional musical score yet again, Kubrick’s use of various classical pieces would create a frightening background of horror-centric music. Compositions would be as symmetrical as Kubrick’s usual imagery, and because of the Steadicam his cinematography would employ an Average Shot Length longer than most films.

He was at this point still in love with the Zoom shot, a technique he would make memorable in numerous films. Contrasting the longer shots is his use of quick montage editing during Danny’s use of “shining”. The Kuleshov effect would again highlight associative editing with images rapidly cut together. By inserting images in successive order, Kubrick is able to have the viewer connect the dots on Danny’s subjective view of the Grady girls (along with a shot of his screaming later in the film) and then the terrifying connotation of the hotel spewing blood out its elevator seen below.

Danny first views the slow-motion shot of the blood flooding out of the elevator, intercut with the Grady sisters holding hands, and with a close-up of his screaming in horror. Not only does this fit within Kubrick’s editorial style, but it thematically foreshadows what he will see in the Overlook hotel.

Cinematographer John Alcott and Kubrick compose many symmetrical shots down the corridors of the hotel

Danny views the dead bodies of the Grady girls in the hallway through quick cuts by Kubrick

Time and space are constantly manipulated. Jack is told of the massacre that plagued the Grady family ten years prior at the hotel, alluding to his own axe-wielding aggressions soon to come. The 1920s frequently make an appearance at the hotel, with the “Gold Room” hosting a party when Jack goes to the bar for another drink, and the final shot shows Jack as caretaker in the photo from 1921 (Grady tells him in the bathroom “You have always been the caretaker here”).

High-key lighting from Kubrick fully captures in close-up the metamorphosis in Jack

Dysfunctional families are hardly new territory for Kubrick, having previously touched on this theme in Lolita, A Clockwork Orange, and Barry Lyndon. It could be said this is Kubrick reflecting a mirror to the Oedipal struggles that plague society. Jack’s exposure to the isolation of the hotel and the demons within literally and figuratively drive him insane and endanger Wendy and Danny. He is forewarned about the abilities of his son and the threat he poses to the massacre about to ensue. Wendy and Danny strive for survival against Jack as they hope to vanquish him and survive together.

“Here’s Johnny!” Another iconic Kubrick close-up.

The production issues with The Shining are legendary. Kubrick shot many scenes over and over again, sometimes shooting more than 100 takes of two actors. He was reportedly annoyed and irritable with Shelly Duvall the entire production, and she was fed up with his treatment of her. If his intentions were to create an anxiety-filled performance, one could say it worked. Is it ethical to mistreat actors in pursuit of a specific performance? Kubrick is hardly alone in having treated cast members horribly in order to achieve a specific cinematic effect. Critical response to the film at the time was mixed. Long time critic of Kubrick Pauline Kael stated: “When we see a flash of bloody cadavers or observe a torrent of blood pouring from an elevator, we’re not frightened, because Kubrick’s absorption in film technology distances us.”

Like most Kubrick films, time has been kind to The Shining and many consider it to be a masterwork of horror cinema, not confined to genre conventions. His ability to work in different genres (war, social satire, sci-fi, noir, horror) and not beholden to genre tropes and instead make breakthroughs for each genre reflects Kubrick’s abilities as an auteur. He innovated the visual style of his horror film, shooting much of it in daylight and with wide-angle cameras to create distortion and deep-focus depth of field–a technique he also used to capture the subjective madness of Alex’s world in A Clockwork Orange. He used horror as a genre for narrative convention, but his own technique and thematic subtext are what make The Shining an adaptation that only Kubrick could make. Kubrick’s ability to adapt The Shining as his film and not a paint-by-numbers adaptation for the King novel shows yet again that Kubrick can make a film only on his terms–and no one else’s.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks