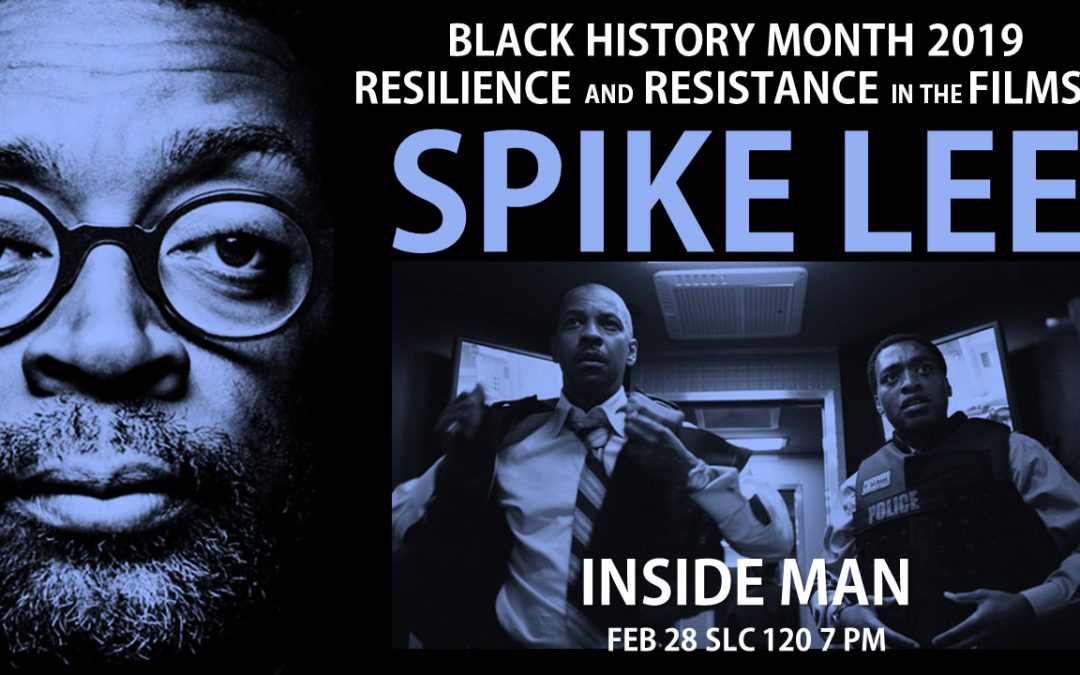

In celebration of Black History Month, the Winona State Spike Lee Film Series concludes with his 2006 hit Inside Man on Thursday, Feb. 28 at 7:00 pm in the Science Laboratory Center Auditorium 120. Typically, the name “Spike Lee” will suggest the following: Righteous indie startup director whose lifelong purpose and drive has been to portray depth and give voice to the African American community with a stylistic panache that ranges from sheer genius to occasional visual nonsense. Viewers have seen this in a countless number of his films, from the great (Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, and BlacKKKlansman) to some much less so. Does a blockbuster mainstream star vehicle filled with action sequences and a linear plotline sound like it fits that mold? Not really, but if you look close enough, Lee’s Inside Man–his fourth film to star Denzel Washington–has enough “Spikeisms” to make the film a recognizable and certifiable Spike Lee joint.

As Spike Lee’s largest box office hit, Inside Man has plenty of aspects that might make you ask, “Are you sure Spike made this?” Unlike his earlier hits, Spike didn’t write Inside Man, nor did he act himself in it, as he had in ten of his own films prior. But still, his fingerprints are all over it. For starters, the first scene is an eye-to-eye first-person shot with the film’s antagonist Dalton Russell (Clive Owen). We’ve seen something similar in She’s Gotta Have It, Do the Right Thing, He Got Game and many more of his films. Viewers don’t know if the person talking is breaking the fourth wall and talking to us, if they are talking to a camera they set up, if they are talking to themselves or if they are talking to a film crew. I don’t know of any other director who does this so consistently. After this first scene, the title sequence plays as another certifiably Spike Lee trait — a long montage of different shots of New York while culturally relevant/ethnic music (“Chaiyya Chaiyya” by A. R. Rahman) plays in the background. Like She’s Gotta Have It, Do the Right Thing, Crooklyn, and others, Inside Man is set in Lee’s native New York.

Spike Lee opens the film up with his famous interview-style face shot of the main antagonist Dalton Russell (Clive Owen)

As the plot progresses, it becomes increasingly obvious that Inside Man is as much as any film a Spike Lee Joint. The film may be relatively linear, but Lee still leaves a little room to play with the progression of the story. For example, when hostages were being released from the bank, they are brought into questioning by Detective Keith Frazier (Washington) and Bill Mitchell (Chiwetel Ejiofor). The two detectives interrogate the people who were released to see if they are the bank robbers. Many times they interrogate someone in a scene and then in another later scene that person would be released from the bank.

Detective Keith Frazier (Washington) and Bill Mitchell (Chiwetel Ejiofor) interview released “hostages”

Lee’s willingness to try different kinds of shots contribute to his status as the first Arfican American auteur. One he is famous for is the “double dolly shot”. This shot includes the protagonist moving toward the camera on a dolly but appears as if he/she is floating while other people and things are moving around in the background. We’ve seen this before in Malcolm X and Crooklyn and Lee employs the technique again in Inside Man with Denzel Washington’s Detective Frazier harriedly floating towards the crime scene. This kind of movement doesn’t make any physical sense in a movie that otherwise completely follows the laws of physics in a realistic way. But Lee’s signature camera movement, like so many of his stylistic traits, not only creates an out-of-body moment for the character but also helps define the director’s own signature style–daring, risky, unusual, visually stimulating, and less concerned with depicting reality than interpreting it. Here’s a catalog of all the times (up to BlacKkKlansman Lee has used it, going all the way back to 1988’s School Daze).

Cultural relevance and social justice issues are what Spike Lee has addressed his entire filmmaking career, from his first feature to BlacKkKlansman. There isn’t any kind of dominating racial theme throughout Inside Man but there are a couple scenes that remind us Lee is behind the camera. The first is when a little African American child is in the bank safe playing his portable video game with Russell. The game is extremely violent game, resembling Grand Theft Auto and even using the “N” word across the screen. The boy explains how the game is about “get money or die trying” (referencing 50 Cent, who is also from New York) using a wide variety of hip-hop African American vernacular. The boy seems to admire the bank robber and shows respect for him in a very calm, under control and mature way. Later on, while being interrogated, he explains he wasn’t scared because he’s from Brooklyn.

I couldn’t help but think this was Spike Lee’s way of casting himself in a movie he otherwise has no particular place in as an actor (unlike so many of his earlier films). Lee also seems to be taking a jab at some of these popular video games for how they portray the black community – nothing but exaggerated violence and gore is portrayed in the five seconds the game is on screen. Later, when a Sikh man who works at the bank being robbed is released, he is beaten by the cops, stripped of his turban, and subjected to interrogation. Lee gives the character, Vikram, a chance to explain the difference between a Sikh and Muslim and how he is consistently disrespected on a day-to-day basis because of his beard and turban. Like the boy and his video game, this scene acts as a relevant social lesson for viewers who don’t know the difference between these people. All the while, the scene calls out police and civilians alike for their xenophobia. And both scenes could come right out of any number of Spike Lee Joints.

Vikram (Waris Ahluwalia) lectures authorities on his personal social injustices

As “non-Spike Lee” as this film might seems, with its star power, slick script, action sequences, and heist plot, Inside Man is very much a Spike Lee Joint in every way that counts. The film is typically considered by many critics to be a top 10 film of Lee’s and satisfied many fans by getting outside of his normal scope and making a kick-ass Denzel action-drama. Inside Man will be the final film in our Spike Lee film series and as always, admission is free to the public. (The film is rated R for violence and language.) We would like to thank the Inclusion and Diversity Office and all of our sponsors for allowing us to help celebrate Black History Month with this deep dive into the work of the African American cinema’s premiere director, Spike Lee.

Recent Comments