Killer’s Kiss (1955)

In the second half of the twentieth century, the concept of the auteur filmmaker had begun to be established by the French New Wave filmmakers. François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard contributed their own work, and they also cited John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Alfred Hitchcock as authors of their own films. Film scholar Andrew Sarris refined the auteur theory in 1962, exclaiming that it required technical proficiency, recognizable style over the course of works, and interior meaning/thematic repetition.

In the mid-1950s, up-and-coming Look magazine photographer Stanley Kubrick had made a few short films but established himself with his first feature, Killer’s Kiss (1955). Many filmmakers got their start with the stylistic approach of noir, an appeal Kubrick couldn’t resist with his low-budget original screenplay. His “one-man-band” production offered him complete control in the form of writing, directing, cinematography, set design, and editing. Like most young filmmakers, complete vision and final cut became an issue: United Artists financed the completed film but opted for a more happy ending against Kubrick’s will. The compromise was only one of few he would make in his career, but the film’s reception from the independent film community was enough to garner future financing and recognition.

Kubrick’s story for Killer’s Kiss is simple enough, a blending of melodrama and noir conventions. Davey (Jamie Smith) is a past-his-prime boxer hoping to escape his low-rent life in New York City. He voyeuristically admires his beautiful neighbor, Gloria (Irene Kane), who also feels trapped at her job as a taxi dancer under the thumb of her obsessive and sleazy boss Vincent (Frank Silvera). Davey and Gloria find a quick spark for each other, seeking to skip town together and escape their downtrodden lives.

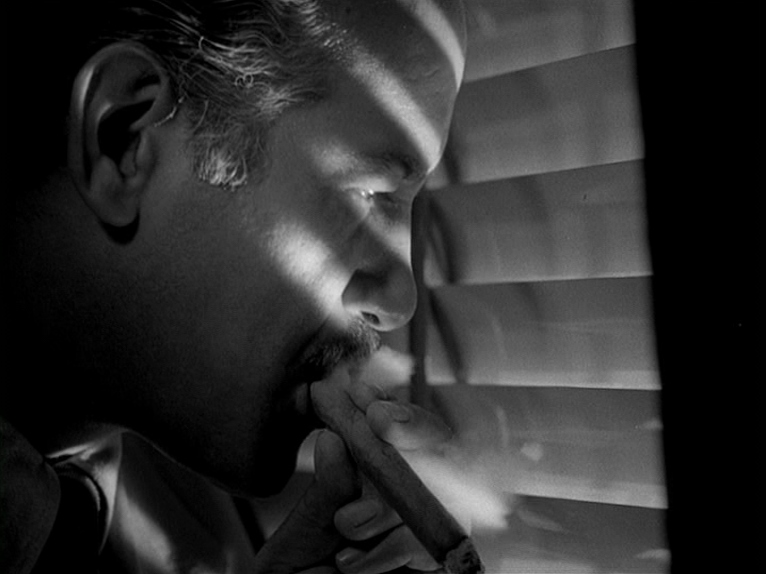

Venetian blinds and heavy shadows exhibit Kubrick’s noir look in Killer’s Kiss (Frank Silvera as Vinnie)

Kubrick grew up in the Bronx, so the location of the film feels very familiar for him. He uses low-key lighting to highlight the contrast of light and heavy shadow found in film noir. While being low budget and essentially still a student film (the twenty-five-year-old Kubrick had some training in still photography, and learned film cameras/editing from books), Killer’s Kiss exhibits professional composition. Kubrick grew frustrated with the sound design captured on set, so he opted for a post-production dubbing of dialogue and heavy use of ambient noise and music. Following in the footsteps of moving camera technique mastered by Max Ophüls, Kubrick establishes his obsession with dolly and tracking shots as well, which will be greater executed in his films to come. His use of the locations and sets he had available in New York at the time were efficient and creative. Deep-focus cinematography captures the details in Davey’s apartment as well as Gloria’s in the background. Rooftop chase sequences serve as exciting platforms for tension and drama. Intimate temporal space in a boxing ring add to the struggle Davey faces in life. Kubrick made the most of what a low budget offered. The dark alley shot below is a staple of noir composition.

Kubrick backlights his NYC alley to accentuate what happens in the shadows

Kubrick plays with some forms of non-linear editing, showing flashback sequences popular in noir for backstory (although they don’t contribute as much to the story as they should). His brief but interesting dream/nightmare sequence — Davey falls asleep and views the negative visual of a dark alley tracking shot capped with screams from Gloria across the courtyard — would be used again in his film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Thematically, Killer’s Kiss sets up Kubrick’s fascination with love and death, and how the two juxtapose with each other beautifully and dangerously. In the very title you see “killer” establishing danger in the story, and “kiss” representing the soft affection of potential love. Davey being attracted to Gloria and the dangerous life she currently lives is a trope of noir Kubrick would return to again in much of his filmography.

Early in his career, Kubrick shows off a talent for composition (Jamie Smith as Davey)

Those who have studied Kubrick know him to be a filmmaker of intense control. His meticulous detail in all the aspect of his films is legendary, with stories from cast and crew ranging from wonderfully bizarre to exasperating. That particular wiring in an artist can be frustrating to those who don’t know how to execute his vision or don’t agree with the collaborative ratio in film making. Kubrick established early on that for better or worse his films were going to be made on his terms. He was also self-critical, disowning his first feature Fear and Desire and deeming it a failure. With Killer’s Kiss he found greater success in honing his craft, and going forward would expand his cinematic scope and affinity for adapting works of literary prowess. When his third feature The Killing was released in 1956, he was an auteur quickly learning from his mistakes and finding his voice.

The Killing (1956)

Producer James B. Harris would take Kubrick on his production wing, and the pair would collaborate in Kubrick’s next three films. In 1955 they received a modest budget from United Artists of $300,000, allowing them to buy the rights to Lionel’s White noir novel Clean Break and cast veteran actor Sterling Hayden in the lead role. Kubrick co-adapted the story into The Killing with hardboiled fiction novelist Jim Thompson, shot by Lucien Ballard, and music by Gerald Fried. Kubrick would create a tight-knit noir that was his most polished film to date.

The plot of The Killing is simple in concept but layered and detailed in execution. In true noir fashion, Kubrick uses voice-over narration to document events of the course of a week, and ex-con Johnny Clay (Hayden) plans one final heist with a group of low-lifes. Over the course of 85 minutes, Kubrick uses a non-linear narrative to show any and all angles of character action as the set-up, robbery, and doomed getaway unfold. He revels in the build up of drama to action saying “At its best,” Kubrick said in a Sight and Sound interview, “realistic drama consists of progression of moods and feelings that play upon the audience’s feelings and transforms the author’s meaning into an emotional experience.” Using this drama to make his audience get invested into his characters, Kubrick creates reasons to not exactly like the sketchy characters looking to make an easy buck, but to see their point of view at all times and want to see the task completed. Framing his narratives around characters with moral gray area would become a common theme with Kubrick, especially the flaws of humanity.

Kubrick’s visual style would carry over from Killer’s Kiss, with low-key lighting and dark effective shadows creating his seedy criminal hangouts. Some of his most effective compositions center around George Petty (Elisha Cook, Jr.) and his wife Shay (Marie Windsor) in their dingy urban apartment. Kubrick allows the tension between characters to linger on during some long takes, and as the meek George promises his wife the life she wants will soon come true, Shay dominates the frame just as her demeanor and sass do to her husband.

Shay (Marie Windsor) dominates the frame vs. her husband George (Elisha Cook, Jr.) setting up the femme fatale’s double-cross

This duping of George Peatty by his wife Shay, with the help of her lover Val (Vince Edwards), feeds Kubrick’s fascination of human relationship with “love” and how it often crosses paths with violence. George and Val up a pawn in Shay’s game, and a deadly confrontation over the robbery loot leads to bloodshed. Violence infiltrates the heist itself, as a sharpshooter takes out a horse with a gun at the same time as a man distracts police at the bar by causing a physical altercation. Such hardboiled noir elements fit Johnny’s plan to steal $2 million from a horse track, representing flaws of desperation and corruption in man. Kubrick’s editing style of showing each meticulous step of the heist works both in “pseudo-documentary” style of storytelling and setting up the drama of the actions for payoff.

Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden) robbing with a mask and at gun point displays Kubrick’s obsession with human violence

At this point in his career, Kubrick was starting to be noticed as a “wonder kid,” an up-and-coming director who was becoming proficient with his craft and who had a singlular vision that the studios mostly left alone to work. With James B. Harris behind him, The Killing was reviewed favorably by most critics at the time, who noted its competent style, good performances, and unique narrative spin made it a notable entrance into the late stage of the noir film trend. Kubrick was a visionary and auteur who at a young age had all he needed to make the films he desired, a trend that would continue the following year with his anti-war film Paths of Glory.

Recent Comments