The times we live in now are strange and still new to many of us. I’m adjusting to the commercials on TV that have adapted to the “new normal” of wearing masks and social distancing. Likewise, it was an odd time to be part of the younger generation during the Cold War. The 1966 film Masculin Féminin, or in English, Masculine Feminine, directed by Jean-Luc Godard, presents a familiar feeling of having to adjust. Jean-Pierre Léaud, who worked closely with François Truffaut in many of his films, plays the main character in this film by the name of Paul. The movie’s abstractness is stimulating and makes some of the narrative’s actions less grotesque, and almost –dare I say– entertaining.

During this period of history the Cold War was going on, and many filmmakers took this as an opportunity to include politics in their films. Masculin Féminin slowly reveals small things in French society that show the hate and stiffness in the air during the war. Godard’s film talks about politics, and his long “fly on the wall” shots and swift set changes exemplify the principal ideals during the French New Wave.

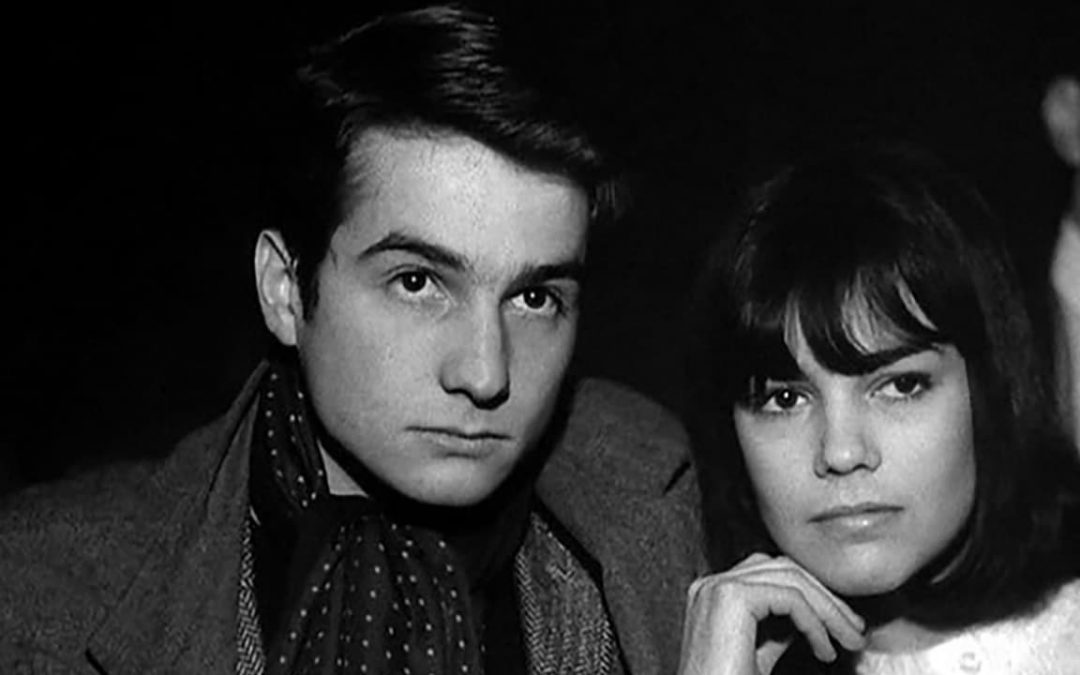

This film’s narrative includes two characters: Madeleine and Paul. Madeline (Chantal Goya) is a rising singer and Paul is an idealist against the war. Madeline and Paul are romantically involved, but when Paul tries to show his love for Madeline, she only accepts it when she feels like it. Paul moves in with Madeleine and her two roommates, and they form a ménage à trois – a group of three people who live together and are lovers. The last half of the film has many one-on-one conversations between the different ménage à trois members. The questions they ask each other seem very demanding and personal, talking about love, sex, and politics. The film follows their everyday lives, whether walking to the café or eating at the dinner table.

Paul talking with his roommate.

The design and cinematography of the movie was lovely. I think Godard had it easy with the set taking place in France since the country itself is already quite sophisticated and beautiful. Many of the settings took place in typical sceneries like cafés, the street, or apartment kitchens. Since the movie used the direct cinema technique, it was important that the scenes looked as natural as possible. There are some scenes where the characters break the fourth wall, looking at us directly through the camera, which lets us know that that part is crucial. I would like to focus on one scene in the movie where I think the cinematography is excellent: we see Paul in a tiny arcade playing skee ball while waiting for Madeleine, about halfway through the film. The camera angle shows us the whole street and Paul peeking through the windows every so often to see if Madeline has arrived. Then the camera tracks backward to reveal a bar on the other side of the street, without cutting. They go and sit together, but Madeleine leaves right away, seemingly annoyed with Paul. Another girl comes up, and again the camera does not cut but instead follows Paul and the new girl to a photo booth next to the arcade. This long-tracked shot not only gives us perspective, but also lets us see time progress as if we were watching them from down the street.

The camera tracking with Paul.

The second camera movement, behind the bar.

The third camera movement follows paul and the girl to the photobooth.

The editing in this film was exciting. From the trailer, I liked how they put the title across the video, but I didn’t know it would follow through to the movie. There were inter-titles of numbers during the film after we cut to a new scene representing that time has passed, and it is farther in the future, at most a week. There were also inter-titles with quotes relating somewhat to the scene that just played.

An example of the intertitles in the film.

This one follows the first intertitle.

An example of what the number intertitles look like that appear in the film.

The music and sound design in the film were mainly comprised of diegetic sounds. The only piece that played in the movie were songs sung by Madeleine. Most times, the music was just the song from the trailer, called Tu M’as Trop Menti, which means You Lied Too Much To Me. The song has a very upbeat 50’s vibe to it, but sad lyrics. During the inter-titles, there was always a specific bang sound that was played every time. It sounded like a sound effect you would use in a video game, and it was most likely meant to grab attention. Since most of the sound was diegetic, the actors had to work around the existing sounds during the shoot. One example of this is the very first scene where Paul is trying to talk to Madeleine, but the busy streets right outside of the café keep him from hearing her too well. When a man walks in and doesn’t close the door, Paul shouts, “The door!” Even with the door closed, you can still hear the sounds of the cars.

The thematic meaning behind this film has been discussed as somewhat of a mystery. Godard presents a few themes in the movie, and all of them could be right, or all of them could be wrong. One theme that I think is central was the competition between genders. There is a scene where Paul and his friend are talking, and his friend mentions there is no masculin without “ass” in it (Cul). They then say there is nothing in the word féminin. By the end of the movie, the title is presented to us one last time and shows us that féminin does have something in it, which is ‘Fin’. Although the letters are not directly next to each other, it makes us wonder. I won’t spoil the ending, but I think the ‘Fin’ in “féminin” has something to do with the last part of the film being that the women in the movie always come out on top somehow, or have better luck than males. Unfortunately for Paul, he sees several acts of violence in the film, such as a man stabbing himself in the stomach, a guy lighting himself on fire with Paul’s matches, and a woman shooting her husband.

Paul catches the man who stabs himself in the chest.

In comparison, the ladies don’t seem much of anything and continue living in dreamland. The numbers I mentioned earlier during the inter-titles could also mean masculine or feminine numbers. Women are mainly viewed as having characteristics of warmth, kindness, and nurturing. For that reason, round, even numbers are associated with females. Males are hardworking and precise, thus related to odd numbers. The numbers were presented in a way that foreshadowed what was going to happen between genders.

All in all, this film is a masterpiece. The film embodied and perfected some of the staple techniques from the French New Wave such as the swift set changes and was still able to make the plot captivating in its abstractness. Masculin Féminin truly did represent the children of the Marx and Coca-Cola Generation.

Recent Comments