In the 34 years between the publication of John D. MacDonald’s novel The Executioners and Martin Scorsese’s 1991 adaptation Cape Fear (borrowing the title from the original J. Lee Thompson adaptation), much had changed about the world. While the villainous Max Cady that MacDonald had written about in 1957 would still be an intimidating figure, he wouldn’t necessarily be a villain that struck fear into the very soul and being of a film audience. So, when Scorsese adapted the novel to the screen, he smartly chose to update Cady (Robert De Niro) into an antagonist whose villainy far surpassed that of MacDonald’s Max Cady. This update of Cady into some sort of “Super-Cady” is most evidently seen as he breaks into the Bowdens’ homestead, an event that takes place at the end of The Executioners, yet just about three-quarters of the way through Cape Fear. Here, Scorsese, DeNiro, and screenwriter Wesley Strick’s Max Cady reveals himself to be a villain far more dangerous and capable than MacDonald’s.

Although Max Cady is the main villain of The Executioners, he disappears about halfway through the novel, becoming more of a threatening presence than an intimidating villain. In fact, after his initial appearances in the first few chapters, Cady disappears from the action, and readers can discern that he is still alive and plotting only through whatever new misfortune befalls the Bowden family. To counter him, Sam Bowden, his wife Carol, and former infantryman Andy Kersek formulate a plan to lure Cady out of hiding: use Carol as bait by giving the impression she is all alone, while the two men wait (Sam in the garage attic, Kersek in the cellar) for Cady to break into the house – as an attempt to kill Cady would then be justified. After rigging the house with noisemaking objects and employing a buzzer for Carol to alert Sam of any trouble, the three take to their respective positions.

After being woken up in the middle of the night by the buzzer going off, Sam – still bleary from the rude awakening – missteps while climbing down the ladder, plunging down the remaining eight feet and spraining his ankle badly. Spurred on by the sound of a scream and two gunshots, Sam forces himself to run the remaining distance to his house. Reaching the door only to find he is locked out, Sam can only listen helplessly as he hears another gunshot. At that moment, though, Cady tries to make his escape. As MacDonald writes, “before [Sam] could move, the locked front door burst open and a half-seen figure, wide and hard and stocky and incredibly quick, came plunging out and smashed into him and drove him back.” Managing to hold onto his revolver, Sam fires off five quick shots in the direction Cady had ran. Sam crawls his way back to the house, where he finds a mortally wounded Kersek, but Carol still alive – just bruised and in shock; narrowly spared from Cady’s attack. Eventually the police make their way to the house, and, after a quick combing of the surrounding land, find Cady dead – fatally wounded by one of Sam’s blind shots.

It is on this anti-climactic note that John D. MacDonald’s novel comes to a close. In terms of adaptability to screen, much about this ending come across as problematic: first, after building Max Cady up to be an omnipotent villain throughout the first two-thirds of the novel, having a stray bullet kill Cady (off-page!) cheapens his reputation as a villain. Secondly, as the novel is told exclusively from Sam’s third-person limited perspective, readers know what is happening inside the Bowden house only from what Sam hears. Film being a much more visual medium, the book’s limited perspective would likely leave the most important action where Sam can’t see or hear it.

Scorsese and DeNiro craft a menacing Max Cady in 1991.

In his 1991 adaptation, Martin Scorsese appears to be mindful of these shortcomings and expertly improves upon the novel’s problems to create an updated version of Max Cady for the late-20th century. To do this, Scorsese changes fundamental details of the house invasion sequence, and moves it to an earlier spot in the narrative. Rather than strictly adhering to Sam’s (Nick Nolte) perspective, Scorsese shifts the scene’s focus to Kersek (Joe Don Baker) as he stands guard over the house. After being alerted of an open window by a fishing line-rigged teddy bear – a nod to the Jerry-rigged alarm system used in MacDonald’s novel – Kersek decides to do a walk-through of the house to make sure it’s secure, finding only the family maid in the kitchen. As Kersek drops his guard to mix himself a Pepto and bourbon, we find out the maid is, shockingly, Cady in disguise, who attacks Kersek with (Chekhov’s) piano wire (its absence having been observed in the first act) and overwhelms him, finally forcing Kersek’s own gun upon him.

Kersek’s point-of-view keeps him from realizing that Cady has disguised himself as the maid.

Alerted by the gunshot, Sam rushes downstairs where, upon discovering the bloody scene, grabs the (now) late-Kersek’s gun and runs outside, firing two wild shots before being subdued by his family. Unlike the novel, however, Cady is long gone by this time; no stray bullet will bring this villain down.

Cady’s powers of deception are nearly superhuman.

Most readily noticeable about Scorese’s update is the choice to keep the Bowdens all together. Rather than having the characters spread out across the Bowden’s property, the entire family – including the Bowden daughter Danny (Juliette Lewis), whose novel counterpart is absent at this point – is located inside the house, effectively bringing the audience inside the house and closer to the action. Utilizing a quick montage of slow-zooming shots, the film establishes a location for each character as they brace for Cady’s attack. Of note, this montage first starts on a shot of Danny, who the film props up as Cady’s main target; as the shot slowly zooms in on her, it’s almost like the audience is seeing Cady’s focus narrow in on her.

Scorsese focuses in on Cady’s target: the Bowdens’ daughter Danielle (Juliette Lewis).

The focus on Danielle also gives Cady’s villainy a modern update: as teenagers were increasingly sexualized in the media, society at large became anxious about the possibility of teenagers being targeted by older men. Further, Cady’s use of cross-dressing to infiltrate the Bowden’s house seems reminiscent of Norman Bates – almost like he’s taking a play from the Psycho (1960, Dir. Alfred Hitchcock) playbook. Through this intertextual scheme, Cady has seemingly become a postmodern villain, willing to use tactics employed by killers of the past to achieve his goal.

Finally, and maybe most obviously, is the fact that Cady survives this scene, unlike the Cady of The Executioners. By placing this scene earlier in the narrative, Scorsese shows that Cape Fear’s iteration of Cady is superior than the Cady of The Executioners – novel-Cady is killed by a stray bullet while trying to run away; film-Cady successfully breaks into the Bowdens house, kills Kersek and the maid, and easily escapes without a scratch. This Max Cady is a villain that succeeds where his novel counterpart fails. This Max Cady is a villain who preys on 15-year-old girls and far more so that MacDonald’s original iteration, a villain for the late-20th century.

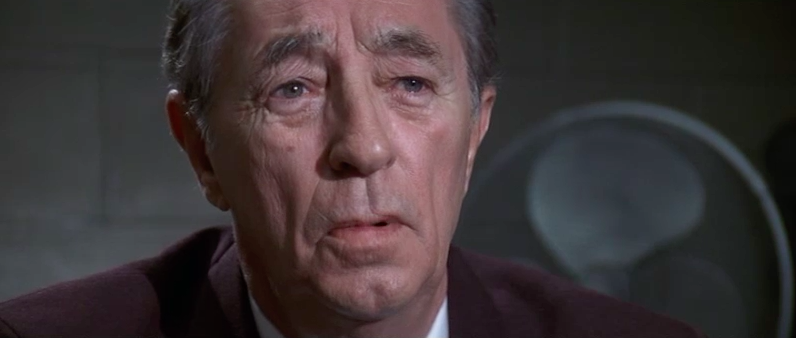

Earlier in the film, Cady had been arrested and forced to strip for a thorough searching by police. As Sam watched through a one-way mirror, he was joined by Lieutenant Elgart, played by Robert Mitchum – the actor who played Max Cady in the initial 1962 adaptation of The Executioners. As the new Cady strips, the camera cuts to the old Cady looking on with horror, as this is a villain so shockingly muscular that even the original actor doesn’t recognize him.

Former Max Cady Robert Mitchum marvels at DeNiro’s Cady: “I don’t know whether to book him or read him!”

Yet, this is what Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear needed; society had changed, and these old villains wouldn’t cut it anymore. At the end of the 20th century, film audiences needed a villain who would succeed where others had failed; someone who would tap into society’s current fears. Film audiences needed Max Cady.

In the end, Sam isn’t even able to take Cady down — only nature is powerful enough to stop him.

Recent Comments