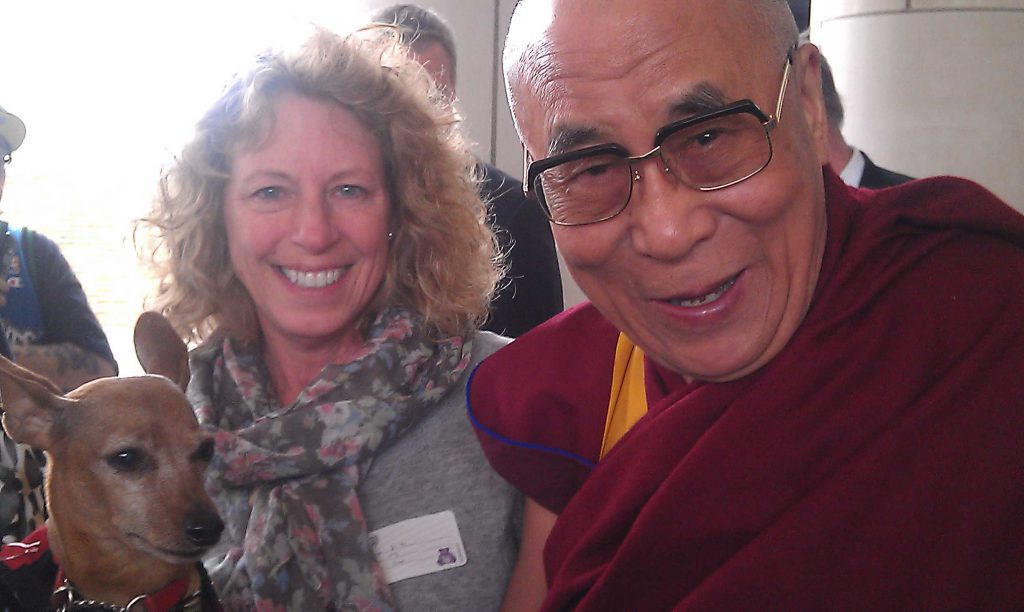

About five or six years ago, my oldest brother wound up getting sick with a bad case of mono and had to go to St. Mary’s Hospital in Rochester for treatment. While he was there, it turned out that the 14th Dalai Lama was also visiting Rochester for his annual checkup at the world-renowned Mayo Clinic there. One day as doctors were beginning to give my brother shots, they ushered my mother out of the room. On her way out, she jokingly said “I’m going to go meet the Dalai Lama!” Lo and behold, she actually got a picture with him and came back with a smile on her face. So, there you have it: the short story of how my mother met the Dalai Lama, the two brought together by their trust and connection to world-renowned The Mayo Clinic.

Ms. Stoulil and the Dalai Lama

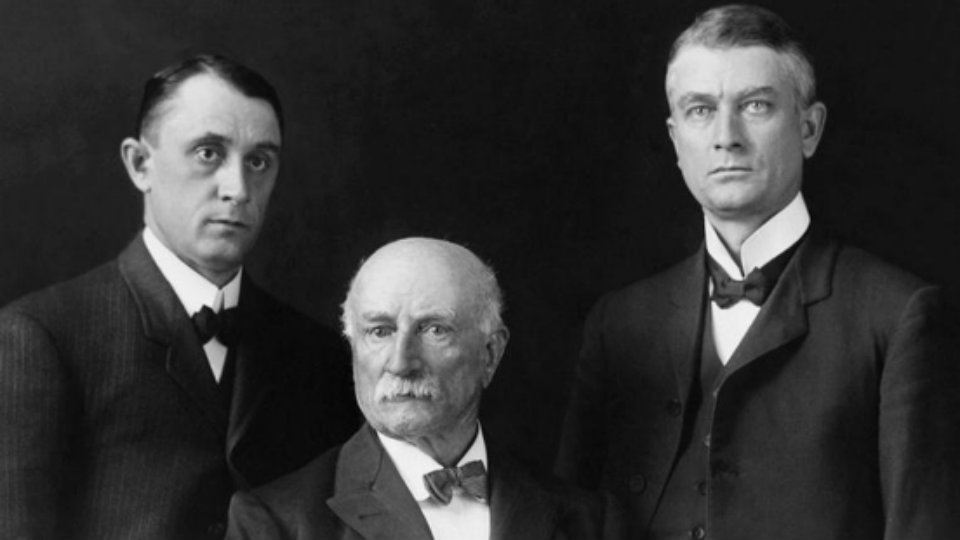

The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science tells the story of how the Mayo Clinic health care company was founded, how it came to be one of the largest contributors to health research, and how its innovative group-led medical practices have put the focus on its patients. The film mainly centers itself on the founders of the clinic, William Worrall Mayo and his two sons William and Charles Mayo. This two-hour documentary produced by Ken Burns, Erik Ewers, and Christopher Loren Ewers was first aired on PBS in the fall of 2018 and has since then been released on numerous online streaming services. From its unique content and cinematic techniques to the subjects being featured, The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science is an aesthetically pleasing production that employs the modes, ethics, and styles, and creativity that goes into documentary filmmaking.

In any documentary, ethics are important. The directors have to make important decisions on what they should and shouldn’t show, talk about, or portray in a certain fashion. They need to obtain permissions from certain premises, as well as the people they plan to interview. In The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science, ethics such as deciding what surgical procedures and surgical photos are appropriate to show, gaining permission to film inside the clinic headquarters, along with setting up interviews with doctors and patients were all considered in the making of the film. Even the ethics of actually shooting the surgeries had to be evaluated, as director Erik Ewers noted that when they were filming the surgeries they had to scrub in and weren’t allowed to touch anything colored blue in the operating room.

The founding Mayo family.

The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science tells the 150 years of history behind the world-renowned Mayo Clinic, a health care company in Rochester, Minnesota ranked the number one hospital in the United States with access to cutting-edge technology for medical research. The Mayo Clinic contains modern footage from the clinic headquarters in Rochester, still shots of the hospitals, surgeons, and nuns from the clinic’s archives, voice-over narration, and interviews with various patients who’ve received care at the clinic. The documentary progresses through its story by switching between the history of the clinic with the Mayo family and stories from the patients who were interviewed at the time of production.

While many of the subjects in The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science were patients undergoing treatments at the time of the filming, a few of the patients were a little more familiar to viewers. Well-known figures such as the Dalai Lama and the late U.S. Senator John McCain were also subjects of the documentary, with the Dalai Lama going to the clinic for yearly checkups and Senator McCain a brain cancer patient. Another notable subject of the film was a patient by the name of Roger Frisch, a world class violinist with an arm tremor who underwent deep brain stimulation to make the tremors go away.

The cinematic styles and techniques used throughout this film fall within the usual documentary film practices. The documentary style that The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science follows is the simple style of normal people going about their lives, not performing their tasks like a paid actor might for a show. Techniques such as one-on-one interviews, capturing live footage from surgeries and using sounds such as heart rate monitor pings to signal the start of a patient’s personal story also add to the cinematography of the film.

The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope and Science employs the aspects of Bill Nichols’ poetic, expository, and participatory modes. The poetic mode can be identified by the descriptive passages and formal organization regarding the clinic’s history, along with the rhythmic qualities of the monitor pings when switching between patient stories. The expository mode makes itself known primarily through the voice-over commentary heard throughout the duration of the film, and the participatory mode is shown through the interviews with the subjects. Each mode has its own style that enhances the documentary, and combining different modes can lead to a richer viewing experience, as it did in this film.

Through content, cinematic modes, and ethics, directors Ken Burns, Erik Ewers and Christopher Loren Ewers were able to take 150 years of history behind a highly-praised medical institution and share its story of medicine and care for others. While weaving in inspiring patient accounts with the hospital, The Mayo Clinic: Faith, Hope, and Science is a heartwarming documentary centered on a long-standing clinic that puts the needs of the patient first.

Recent Comments