The classic tragedy: The hero wants something more in life, goes to search for it, overcomes the roadblocks, slowly sees the plan start to fail, and finally meets their demise. For a character in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960’s film, A Bout de Souffle, or in English, Breathless, this couldn’t ring more true. But, is he the main character that he thinks he is? Or is he just another pawn in the grand scheme of things for someone else? Godard creates a contrived love story between two people through the romanticization of their ideal lives. Patricia, a woman who wanted her breath taken away, and Michel, a man who was longing to start over.

Godard was a part of the Cahiers du Cinema (Notebooks on Cinema), a magazine devoted to film and film criticism. Several other notable French New Wave directors that were part of the magazine–such as Francois Truffaut or Claude Chabrol–started making films that broke away from the traditional storytelling method. This new movement aimed to treat the movie as its way of telling the story. New techniques emerged from the movement, such as long takes and more focus on mise-en-scene. Doing these techniques allowed directors to start putting more of their personality and vision into the story instead of just playing it by the script. With Godard’s extensive history of film critique from Cahier du Cinema, recognition from other works of his, and working with François Truffaut on the initial script, he earned the funding he needed to start making Breathless.

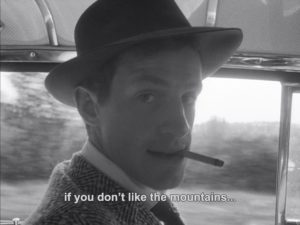

In the first scene of the film, we begin with a character named Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belondo) saying, “After all, I’m an asshole,” then, with pursed lips, he runs his thumb over them. If this is the first sentence we hear from him, it lays out the rest of the film. He touches his lips because he models after Humphry Bogart. Bogart starred in lots of films that portrayed him as a rough-and-tough gangster character. We soon enough see that Michel stops by a movie poster of Bogart with his thumb on his lips and mimics it, indulging in his perfect form. Michel later steals a car and we ride in the front seat with him. He breaks the fourth wall and talks to the camera, as he rambles on about women and France. Breaking the fourth wall was new and not a commonly known technique at the time, and even today, it is used seldom. Although it doesn’t provide us any more knowledge that could be useful in the rest of the film, it does allow us to feel more connected to the scene. In some way, it introduces us to him directly, without the storyline.

Michel breaking the 4th wall.

While speeding down the road, a policeman pulls him over, and Michel shoots him. We never physically see Michel shoot; we must connect the two scenes and the sounds. There is an extreme close up shot of the gun shooting and a jump cut to the policeman falling over in the brush. Instead of smoother editing, using jump cuts is more sporadic and reiterates Michael’s hasty choices, and that he does not regret it. There is some emotion with the extreme close up of the gun because it depicts its power by filling up the entire screen. Usually– at least for me– when I see somebody get shot in films, it’s not the gun itself that I feel threatened by, but the image of somebody being shot. In contrast to this film, when the policeman falls, his face is not shown, adding some dissociation. Thus, the emotion is put more on the gun than the policeman that got shot. Focus is brought back immediately on Michel’s escape with the final jump cut. The intro spotlights Michel well enough so we can gauge his personality – there isn’t much to him besides being a want-to-be-gangster that makes poor choices.

The close up of the gun.

The police man falling into the brush.

Once he makes it to the city, he meets up with Patricia, who finds the key to her apartment missing. She goes upstairs and finds Michel, the culprit of the key snatcher, in her bed. The next twenty-five minutes of the film take place in her small room and connected bathroom. Michel and Patricia talk about life. She mainly focuses on sad, existential topics, while Michel only cares about running away to Italy with her, her body, or having sex. Underneath all of the sensual conversations, it’s obvious Michel is deeply in love with Patricia, but the only way they can start a new life together is by moving out of the country. This is why he tries to convince Patricia to leave with him. Patricia does not know if that’s what she wants to do, so she keeps leading him on. Michel makes faces at her while talking, which implies he thinks she is too dramatic, though Patricia thinks it suits her just fine. Having the scene be so long is a little dull after the first ten minutes since it’s a continuous loop of Michel wanting Patricia while she isn’t interested. However, the length does help illustrate the dichotomy between reality and illusion with the two characters. They romanticize their characteristics and the topics they discuss, but it’s countered by the banal location.

Michel and Patricia in her apartment.

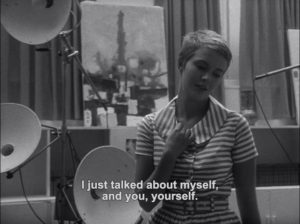

In Godard’s films that I have seen, he seems to keep a consistent theme on the younger generation and their everyday lifestyle. One of my favorite quotes from Patricia is, “I don’t know if I’m not happy because I’m not free, or if I’m not free because I’m not happy” (Breathless). Rather than a familiar and comforting narrative that requires no thought, Godard provokes the audience to think twice about what matters and how we achieve it, especially in Patricia’s case.

On top of that, the love story itself is something to think further about. Patricia has an up-and-coming career in journalism and can take care of herself without others’ help. Yet, by bringing in Michel, it questions her freedom and needs. The love she feels for him could compromise her aspirations. In my opinion, I believe Patricia knows what she wants and is sure of herself, and while meeting Michel was not part of her plan, she enjoyed having somebody to spice things up. In turn, she keeps him around for fun. Godard essentially asks us how love affects and defines the way we perceive our life choices. By the end, Patricia turns Michel into the police, ending her charade and confirming that she wants to be independent.

Patricia after she tells Michel she called the police.

While leaving, Michel gets shot by the policemen, which is similar to the first shooting scene. The police shoot, but we do not see the bullet hit Michel. It cuts to Michel, holding his lower back and staggering down the street, which happens in one long take. He manages to walk down to the end and we watch him fall on the pavement by a busy intersection. This scene is accompanied by very jazzy music, adding to the dramatics of his death. Patricia stands over him as he is lying on the ground. He makes the same three faces to her as he did when they talked in her apartment. Michel is doing the faces as his trump card. Patricia thought she was perfecting her craft of romanticizing her own life, but Michel got shot, which is more real than her problems could ever be, and he’s still not being overdramatic. Well, maybe a little, by having to stumble down the street and flopping down like a seal doing a trick. He tells her, “You make me want to puke.” She asks the police what he said, they reply, and she says, “What does ‘puke’ mean?” as she looks directly into the camera and rubs her fingers over her lips. This is the second fourth wall break in the film. Unlike the beginning fourth wall break, this one retains information that is useful to the meaning of the ending. By looking directly into the camera, it signifies that it was all fake. Since Humphry Bogart was an actor, and they both do his signature lip, it makes sense that it was all an act. At this part of the film, I realized that Patricia did not care for Michel. She wanted all of the dramatics to happen, which is why she romanticized her life so much, and by dating an on-the-run-criminal in Paris, it added the exact flare she was looking for. Although she did what she thought was best for her, the cost of her independence was, sadly, Michel’s life. Instead of him taking her breath away, she took his away, and instead of Michel starting over, she was able to start over. Godard took this love story and transformed it into an allegory of self-actualization.

Recent Comments