Drive is a 2011 neo-noir film directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, starring Ryan Gosling as an unnamed Clint Eastwood-like loner, referred to as the Driver. The Driver doubles as a mechanic at an auto body shop and a Hollywood stunt driver with his business partner Shannon (Bryan Cranston), while also quietly taking jobs as a getaway driver for bank robbers around Los Angeles. Living a relatively lonely life outside of his friendship with Shannon, the Driver unexpectedly begins building a strong relationship with a single mother named Irene, played by Carey Mulligan, and her son Benicio, who both live down the hall. As the relationship prospers, the Driver attains a meaningful purpose stepping in as a father figure for Benicio and a romantic interest for Irene, filling the void left by Irene’s husband and Benicio’s father, Standard, played by Oscar Isaac, who has been incarcerated in prison for the last several years. Standard’s prison time, however, is cut short, wedging him unexpectedly back into the lives of Irene and Benicio, closing the Driver off from them. When prison debts catch up to him, Standard and his family’s lives are put into danger, prompting the Driver, out of concern for Irene and Benicio’s safety, to step in and utilize his skills to protect the ones he loves.

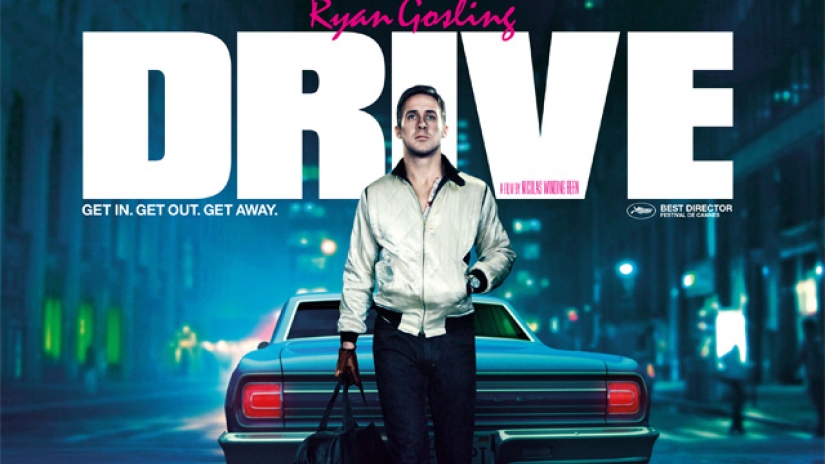

The visualy striking poster from the 2011 thriller.

Upon examination of the underworld depicted in Drive, one finds many qualities integral to both classic noir and neo-noir. In this underworld, audiences are exposed to a variety of shady characters with unclear motives and histories. Besides Irene and Benicio, these shady characters are the central players in the film. The script hints but never fully explains the complex criminal web that connect all these characters, but it is clear they are all tied into the same crime. As with most noirs, the labyrinth of the underworld and the vile act of which the narrative revolves around are brimming with twisting and curving plot points, creating a world of intrigue and mystery very similar to the one intertwining the characters of Drive. Set in Los Angeles, a staple of the noir genre as evidenced by such films as Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard, Chinatown, The Player, L.A. Confidential, as well as many others, Drive capitalizes on its stylistic urban landscape. Like the earlier mentioned Sunset Boulevard, The Player, and L.A. Confidential, Drive infuses its underworld with the idolized land of Hollywood, depicting a darker, less romantic version of the “film production Mecca”. However, not all aspects of Drive’s L.A. are unromantic. The city’s beautiful skyline is infused with the stylistic intro of the film, featuring the insomniac the Driver wandering street-to-street, to escape the loneliness of his apartment. These eye-popping neon images breathe a romantic life into the world of Drive that, compounded with the frighteningly realistic aspects of the narrative, balance out the film’s tone in a uniquely interesting manner.

One of many stills from the film which capture the nightlife of L.A. in colorful fashion.

Drive features a very neo-noir setting in its corrupt L.A. cityscape, a piece that helps distinguish the films texture and style as a neo-noir itself. The film’s style is not completely conventional however. Winding Refn emblazes the screen with a clearly eighties-inspired touch. Synth music rumbles out of the soundtrack, neon pink font furnishes the opening credits, and the Driver, himself, wears an eighties Kiss-inspired scorpion jacket. These features allow Drive to develop its own memorable personality that separates it from the crowd of other neo-noirs. Aside from this, Drive is a neo-noir so it certainly conforms to other conventions of the genre. Such aspects such as its effective uses of low key lighting, its hyper stylistic violence, and film’s tendency to throw the audience into events rather than offer up extensive narrative exposition explaining the situation. These are all key pieces of the film’s style and absolutely essential to illuminating the world of Drive onto the big screen.

An example of the film’s unique fusion of noir with 80’s style.

Perhaps the most interesting echo of noir tradition that is visible in Drive is characterization of the protagonist. Ryan Gosling’s Driver shares more in common with neo-noir protagonists Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver) and Lou Bloom (Nightcrawler) than conventional noir protagonists Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon) and Walter Neff (Double Indemnity). Like Bickle and Bloom, the Driver is a lonely insomniac who indulges in violent outbursts to protect something valuable to him. With Bickle, it is an obsession to rid the streets of all things indecent to him. And with Bloom, it is an obsession with furthering himself in competitive world of news journalism. The Driver features a more romantic driving force, as his main ambition is protecting Irene and Benecio, but this does not make him immune to his moments of the shameful behavior exhibited by his noir protagonist counterparts.

The Driver’s latent rage is evident in the film’s gruesome elevator sequence. In it, audiences are treated to an elongated moment of Hollywood romance as our hero leans in to kiss our damsel, pushing her out of the way of an assailant in the process. This moment is amplified by a beautiful ambient synth score residing in the background. Events quickly take a dramatic turn, however, when the Driver turns around immediately following the kiss, and, in an absorbed act of pure rage, stomps the assailant’s face into a puddle of mush. Irene, witnessing this new side of the Driver, retreats in fear and disgust. This instance of the protagonist being rejected by the woman who pulled them into their circumstances is picture perfect noir. It’s clear, however, that the Driver’s depiction, still differs dramatically from the depiction of his counterparts Bickle and Bloom. Unlike Bickle and Bloom, the Driver is still often regarded in heroic reverence as a selfless wanderer similar to the Man with No Name from Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy and Max Rockatansky from George Miller’s iconic Mad Max franchise. This is evidenced by Irene’s eventual forgiving of the Driver’s violent acts when she knocks on his door at the very end of the film, as well as the Driver’s redemptive near-sacrifice in the film’s climax, followed by shots of him riding off into the sunset. Drive takes the world of neo-noirs and illustrates them with a fairy tale grace that is clearly evident in the characterization of Gosling’s Driver.

The romantic and horrific scene the Driver shares with Irene in the elevator.

Drive explores the genre of noir that, through its second coming re-incarnations of neo-noirs, has near infinite potential beyond its neon palette. Whether it be through the familiar setting, style, or protagonists, Drive demonstrates it has a strong grip on what makes a noir, while also demonstrating an ability to manufacture its own unique style that coincides, honors, and re-invents the tradition.

Recent Comments