I’ve heard of ménage à trois before, due to Jean Luc-Godard’s 1966 film, Masculine Feminin. However, it’s still a rare occasion to see two best friends in love with the same girl, all living together, and having an open relationship – or, in this case, a one-sided open relationship. Francois Truffaut’s 1962 film Jules and Jim centers around a pair of best friends named, you guessed it, Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre). Jim is French and Jules is Austrian, but they both fall for a woman named Catherine (Jean Moreau), who looks like the Greek goddess of love, Eros. While things go smoothly for a while, the trio experiences a split due to Catherine’s challenging love game.

The film was based on Henri-Pierre Roché’s 1953 semi-autobiographical novel that he published when he was seventy-four. Truffaut had found it at a secondhand shop, immediately saw its potential, and mentioned it in one of his film reviews in the Cahier du Cinema magazine. After seeing Truffaut’s kind words, Roché reached out to him with his second book, Deux anglaises et le continent, and Truffaut instantly fell in love with his second novel as well. A friendship blossomed, and they talked often. Truffaut was so passionate about the novel that he started writing a script and adapting it for the screen, but due to its sentimental value to both Roché and Truffaut, he postponed the film until he felt the story was truly ready. Truffaut kept in touch with Roché until Roché’s passing on April 9, 1959. After that, Truffaut became the filmmaker we know him as, coming out with The 400 Blows and Shoot the Piano Player. Since Shoot the Piano Player was a commercial failure, Truffaut decided to make Jules and Jim come to life, with production of the film finally starting in 1961.

Upon release, the film was a smash hit with the younger generations. During 1966, the second wave of feminism was on-going, so Catherine’s representation of the idea that the female gender is always demanding equality from their male counterparts really resonated with audiences. Another factor that grabbed the younger generation’s attention was that all three members of the ménage à trois seemed to be carefree and lacked the societal chains that separated them from traditional ideals and societal norms. These were ideal principals for the rebellious teens of the ’60s. An example of this in the film would be that Catherine dressed up as a man — she even drew a fake mustache on and everything — and all three of them paraded around town with their new friend Thomas. In 1912, I’m sure that would be highly unconventional, but they didn’t care.

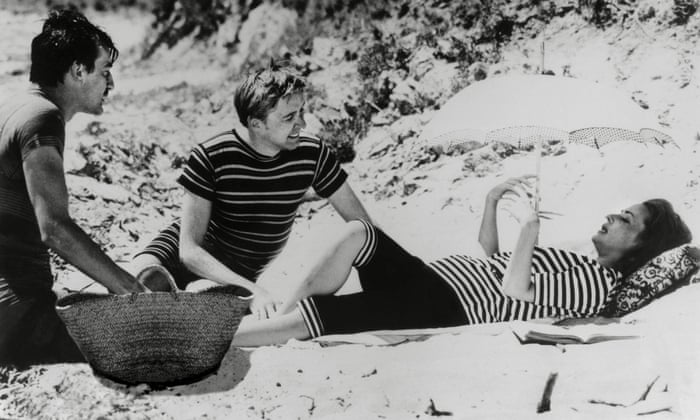

Jules (Oskar Werner, back) Jim (Henri Serre, front) and Catherine (Jean Moreau, left) talking about her mustache.

Truffaut took real pieces of dialogue from the novel and used it in the film to stay as true to his old friend’s story as he could, including other details like having the story be set in 1912 as it was in the book. He knew Jean Moreau from meeting her at the Cannes Film Festival and just knew he had to cast her as Catherine. Werner was Austrian and Serre was chosen due to his close resemblance to a younger Roché. At the beginning of the film, we see that Jules and Jim are the best of friends and did just about everything together until they meet Catherine, and Jules asks her to marry him. The trio seems blissfully ignorant towards societal norms and standards, Jim seemingly unbothered about his best friend marrying Catherine until World War I hits. Since Jules is Austrian, he fights on Germany’s side while Jim stays and fights for France. During their time in the war, both men were frightened that they would accidentally kill each other on the battlefield. Luckily, both of them survive and meet up again after the war, about one-third of the way through the film. At this point we also discover Catherine has not been an agreeable wife to Jules after the two friends catch up after being separated for so long. Slowly, Jules realizes that Catherine is no longer truly his wife. She has affairs with other men without regard to his feelings and she lashes out at at him if she does not receive what she views as proper appreciation.

Catherine talking with Jim about her marriage to Jules.

The film shocked me since the story went in a different direction than what the beginning credit sequence made the film look like: all laughs and giggles. Plus, the criterion channel thumbnail was of all three of them smiling and looking like they were having a good time, but eventually, the film feels morbid and dismal due to Catherine’s irregular love language. Truffaut certainly has an excellent taste for stories that are a little depressing, considering his own childhood story – told in The 400 Blows – which was a bit bleak as well. Nonetheless, the film presents life realistically, showing it is not always rainbows and sunshine. Besides showing Jim and Jules how to demonstrate indifference to what others think of them, Catherine also pushed them to other limits by constantly testing their love for her, and even presenting the choice between life and death. As Aristides Gazetas says in his textbook, An Introduction to World Cinema, “The frighting premise that emerges from Jules and Jim is that the lovers can only liberate themselves from the tyranny of existence through playing out adult games and rituals that lessen the unpredictability of their lives” (217). In other words, although their freedom might seem genuine and believable, they are only playing along to what Catherine wants so they can live a life of peace. In the end, Catherine’s state of mind becomes foggy and she ends up driving her car, with Jim in it, off the edge of a broken bridge – right in front of Jules.

Catherine driving off the bridge with Jim in the car.

The French New Wave has reached about every corner of the earth but primarily affected American Cinema, specifically New American Cinema, and vice versa. Jules and Jim is acclaimed for its bold themes of love, fidelity, and obsession. New American Cinema — similar to France’s changing styles — strived to break away from studio reign and wanted to express more of the uprising counterculture, especially during the 1960s when there was so much going on in the U.S. Directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles, who made big strides in American cinema, were an inspiration to Francois Truffaut and Godard, each country always seeking inspiration from each other. Jules and Jim was the tiny raindrop that created a whole ripple of bold-themed films, like Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Taxi Driver (1976), and even The Godfather (1972).

Recent Comments