Beginning with images of a swan swimming backwards and ending with a montage of a car wash, Sandi Tan’s film, Shirkers, is one of the most idiosyncratic documentaries of 2018. Logically, the film shouldn’t work––it’s an avant-garde film within a film, a nostalgic look at childhood, and an unsettling mystery all in one, narrated by a dryly humorous narrator with an undying passion for cinema. Beginning as an artsy 1992 movie made by teenagers and their on-again, off-again adult mentor, Georges, Shirkers was to be the first Singaporean road movie until Georges spontaneously kidnapped the footage and disappeared. What follows is a 26-year investigation into where Georges and the footage went, why he disappeared, and how Tan and her friends reclaim what is rightfully theirs following his nonsensical betrayal.

The film is pieced together like one of the teens’ magazine cut-out collages: a work of sloppy perfection featuring images, like the swan and the carwash, that have no bearing on the narrative but overall contribute to the quirky sense of mise-en-scène . The scenes are an amalgamation of b-roll, punctuated by Tan’s narration and interrupted by modern-day interviews with her friends, who are continually correcting her reminiscences with explanations of what really happened, much to Tan’s dry amusement.

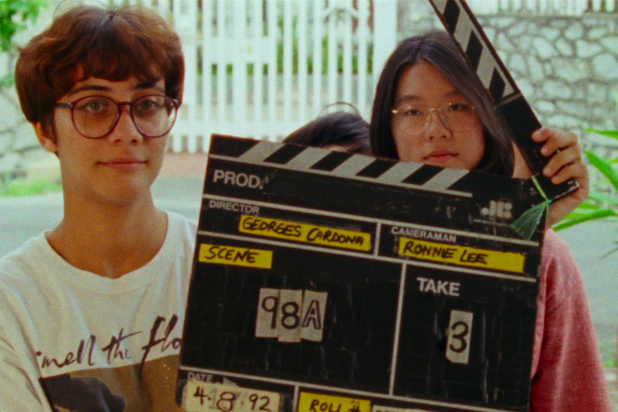

In 1992, Sandi Tan and Jasmine Ng began a collaborative punk-inspired film that disappeared for decades.

The editing greatly lends itself to this bending of time and Tan makes use of techniques such as playing the footage backwards to illustrate her movement back in time, like with the opening shot of the swan. Sound effects are also used to great extent to punctuate cuts and bring to life otherwise silent elements of the b-roll.

The brightly colored footage and nostalgic images of teens happily making a film are contrasted by the sinister musical score, which at times feels like it belongs to a horror film, contributing a genuine sense of creeping unease, especially where Georges is concerned. Tan builds his character out of retrospect, presenting every red flag about him with the ironic perspective of her younger self who was blissfully unaware of what was to come.

The teens’ film project also adds elements of discord. Featuring young Tan in the lead role as a sixteen-year-old serial killer who is simultaneously trying to save and kill just about everyone she runs into (her victims dying bloodless deaths at the hand of her finger pointed into a gun shape), the 1992 version of Shirkers reads as part abstract art film, part enthusiastic teens mimicking their favorite violent dramas with no budget. Tan’s narration wryly notes the quirkiness of this plot line, making no real attempt to explain it other than what it meant to her and her friends at the time. As one of Tan’s friends notes, “The plot was irrelevant.” It is the teens’ earnestness that drives the heart of the film and convinces skeptic viewers that what they were making was truly genuine, if not great.

Mentor-turned-filmnapper Georges Cardona’s presence haunts Tan and her film even in the present day.

This unparalleled love for cinema only makes Georges’ actions even crueler and more incomprehensible. The pain that Tan and her friends display while discussing it in modern-day interviews only drives the stakes higher for Tan to crack the case and find some semblance of closure for this turbulent period in their lives. Shirkers very much belongs to the performative mode of documentary, with Tan spending the majority of the film either narrating over footage of her younger self or narrating her investigation into Georges’ disappearance. This is only fitting, as Tan is just as much of the driving force of the 2018 film as she was in 1992. While her friends are supportive of her mission, they essentially want to just move on with their lives, making Tan’s character into a sort of private eye who will not quit long after others have abandoned the case.

While Tan eventually does find some answers, the results are mixed for her and her friends. This is where the performative nature proves essential because the real triumph for Tan is the existence of the 2018 film itself. By creating this film, Tan not only defies her former mentor’s attempts to quell her dreams––the “vampire of cinema,” she calls him––she also achieves lasting success with the win of Sundance’s 2018 World Cinema Documentary Directing Award and an acquisition by Netflix.

While 2018’s Shirkers is an entirely different story than the fictional 1992 version, its inherent spirit is the same, albeit with a more seasoned perspective on life. Fundamentally, Tan’s work is a tribute to both her childhood and her friends, and it proves that despite Georges’ best attempts, Tan is a renegade director who cannot be stopped, even if it takes her 26 years to achieve her film.

Shirkers (2018) is currently available on the subscription service Netflix.

Recent Comments