Since the beginning of the War on Terror with the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and then the invasion of Iraq in 2003, there have been many films documenting and analyzing the conflict. From action films like The Hurt Locker (2009) to documentaries like No End in Sight (2007), filmmaking has been an avenue in helping the public process the experiences that war brings. No different from this is the 2018 documentary The Interpreters, a film that effectively brings to light a very specific and current issue of the war that has long been improperly addressed. The film is most effective in its message due to the timing with which the creators orient audiences in the story––not at the beginning but in the middle, with much in the past to reflect upon and much in the future to experience, allowing audiences to feel a part of the story as it unfolds onscreen.

The Interpreters first premiered at the 2018 Mountainfilm Film Festival in Telluride, CO, winning both the Student Choice Award in addition to the Moving Mountains Prize. Directed by New York-based filmmakers Andres Caballero and Sofian Khan, the film follows three Iraqi and Afghan interpreters who assist the U.S. military in communicating with local groups. While the interpreters perform invaluable service and are paid by the U.S. accordingly, this assistance also renders the interpreters as traitors in the eyes of their country, ensuring certain death if their identities are discovered. The film follows the successes, struggles, and tragedies that interpreters Malik, Mujtaba, and Phillip experience as they attempt to obtain visas and escape with their families to the U.S.

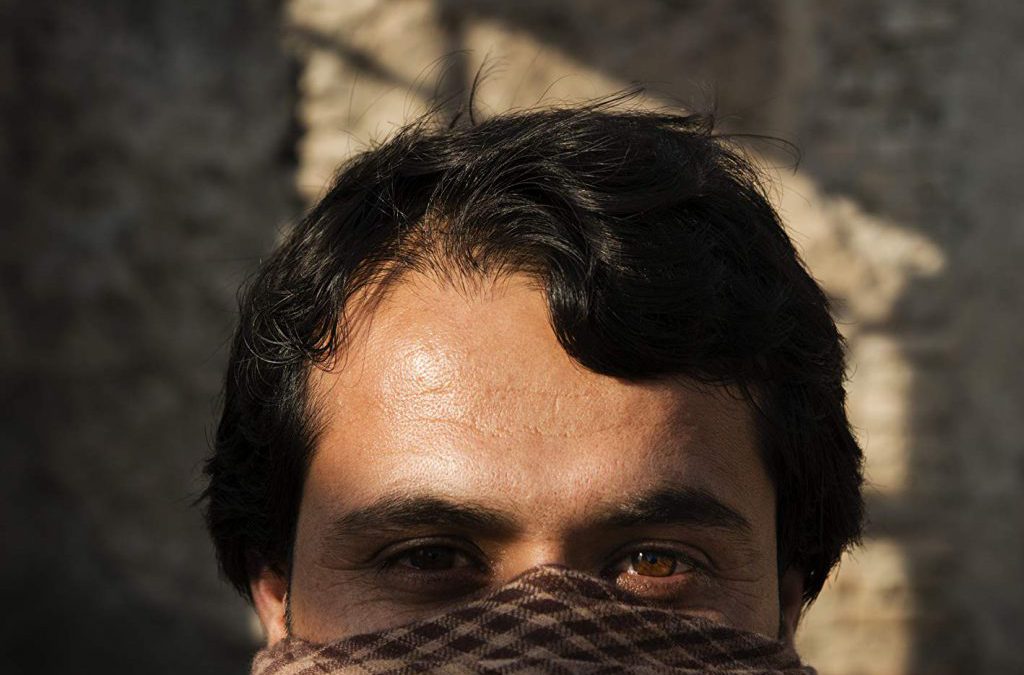

The film required significant ethical considerations on the part of the filmmakers, considering that their subjects were continually in grave danger. Out of concern for his true identity being released, Malik wears a bandanna obscuring the lower half of his face for much of the film––a striking visual that becomes an immediately recognizable image used in promotion for the film.

With the challenge of capturing these highly sensitive situations, directors Caballero and Khan adeptly combine interviews and observational filming alongside subject-shot footage for the moments that the filmmakers cannot capture themselves. The editing is relatively unobtrusive and for the most part, the filmmakers attempt to stay out of the way of the audience’s attention, rendering the film with a highly realistic feel as opposed to a stylistic one. For the most part, the subjects are allowed to simply tell their stories––all of the shaping that must occur presumably occurs off screen. The film employs Nichols’ participatory mode of documentary, where the presence of the camera is not ignored but is not made the focus of attention either.

Featuring footage shot in both the U.S. and the Middle East, the film first acquaints viewers with U.S. soldier Paul Braun as he recounts meeting his interpreter, Phillip, for the first time and how they bond, eventually becoming best friends. As Paul’s time in the service comes to an end, he begins to wonder what will happen to Phillip, who is caught between worlds. It is at this point that the perspective shifts largely from Paul, who is back in the U.S. and working to bring Phillip to safety, to the interpreters themselves. This method of storytelling is particularly effective as it acknowledges the history of the war that American viewers should be familiar with before introducing the relatively new idea that these interpreters have been assisting all along. Viewers, having heard testimony from a U.S. soldier about the validity of the interpreters’ assistance, now have a sense of trust and attachment to the interpreters, who may otherwise have been viewed with distrust given their nationalities.

“Phillip Morris” and Paul Braun.

After receiving the interpreters’ accounts of their experiences, the film shifts from telling the story in the past-tense to the present-tense. This transition emphasizes to viewers the immediacy of the danger the interpreters are now facing as a result of their past actions. This is particularly effective in that it allows audiences to live the experiences along with the interpreters themselves. Not knowing what the fate of the subjects will be, the audience is encouraged only to become more invested as the film progresses.

By the film’s end, viewers are increasingly aware that while the film’s interpreter subjects number in only three, tens of thousands of interpreters are stuck in similar plights, leading audiences to a clear call to action that something must be done to assist. Thanks to the film’s efforts to allow the issue to unfold as opposed to just telling about them, audiences are left with a strong sense of investment. Overall, The Interpreters does an excellent job of cultivating audiences’ sense of trust by its careful manipulation of time and it leaves viewers with an entirely new perspective on a highly storied war.

Recent Comments