Thanks for joining me as I continue to analyze the science-fiction genre in my film criticism series. My last post focused on Rise of the Planet of the Apes and its ideas of undeserved power and questionable personhood. Today, I am looking at Denis Villeneuve’s latest sci-fi epic, Dune (2021).

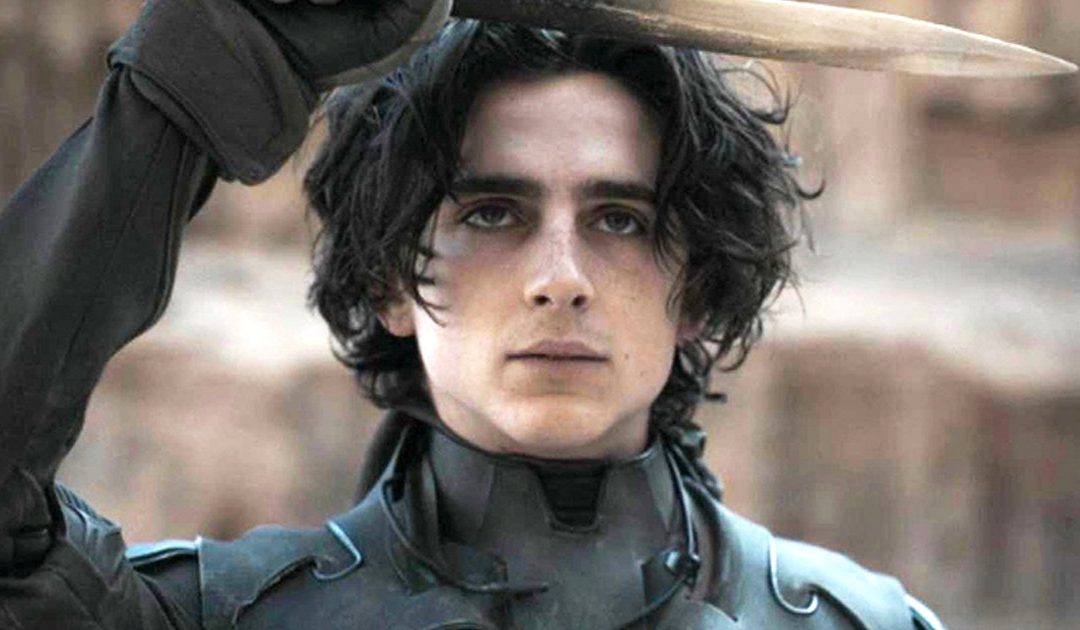

John Connor. King Arthur. Jesus Christ. The crux of the western messiah archetype is precisely identified by Oscar Isaac’s Leto Atreides: “A great man doesn’t seek to lead. He’s called to it—and he answers.” A messiah is not so by choice or because he seeks power, but because he was born to be. Because he fulfills his destiny. In his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s iconic novel Dune, the progenitor of modern science fiction, Villeneuve masterfully incorporates both generic and religious conventions in order to craft a savior character that resonates deeply with its audience. In Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), Dune provides the ultimate messiah archetype by combining components of both Christianity and science fiction.

Dune likens Paul to Jesus Christ, the quintessential messianic figure, through many parallels. In the Hebrew tradition, the Messiah is the subject of thousands of years of prophecy, anxiously awaited by the Jews. Some believe he has yet to come, while others (namely Christians) believe he has already arrived. Likewise, Paul learns from his mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) that the Bene Gesserit—a powerful religious organization whose ways she has been teaching him—have been preparing for a savior called “the One” for millenia. “We think he’s very close now,” she tells him. “Some believe he’s here.” It is implied that Jessica, as well as some others, believe that Paul is the One. When they arrive on Arrakis, a planet over which the Emperor has granted control to House Atreides, she explains to Paul that the Bene Gesserit have been “preparing the way” for the One by planting prophecies among the Fremen, the planet’s indigenous people. This is reminiscent of Matthew 3:1-6, in which John the Baptist cites the prophecy in verse 3 of Isaiah 40: “Prepare the way for the Lord, / make straight paths for him.” He goes on to baptize the people in order to prepare them for their Savior’s arrival. And in a fashion not unlike Jesus referring to himself as “the way” in John 14:6, the Bene Gesserit refer to their traditions and spiritual powers as “the Way.” The parallels continue: Jesus is said to be the king of his people—the Jews—but also a savior and leader to the world: gentiles, sinners, and all. Mirroring this, Paul becomes the Duke of House Atreides upon his father’s death, but he is also ostensibly destined to be the Fremen’s savior, and he plans to become ruler of the entire galactic Imperium. Finally, just as King Herod ordered his men to massacre all Hebrew newborns in a failed attempt to eliminate the threat of the supposed king of the Jews, the Emperor sends his army to wipe out House Atreides, whose leadership among the houses threatens him, but fails to kill Paul.

Dune further establishes Paul as a messiah through its implementation of nonlinear chronology, a common semantic element of science fiction. For sci-fi saviors, “prophecy” typically comes in the form of knowledge of the future. Often, this knowledge ends up being the very reason for the messiah’s existence, creating a time loop. Take James Cameron’s The Terminator (1985) and its sequel Judgment Day (1991) for instance: John Connor (Edward Furlong) is born only because Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn) travels back in time to ensure the war hero’s safe birth and subsequently falls in love with his mother, and Connor goes on to save the world only because he has been raised with the knowledge that he will. Similarly, Paul, who initially rejects the idea of being the One, has visions of the future induced by the psychoactive Spice which imply that he is. As his premonitions continue to come to pass, Paul begins to accept his destiny and allow the visions to guide him on his path to becoming the One. Therefore, his knowledge of the future is what causes this future to come into existence in the first place, reinforcing the idea that it is Paul’s destiny. Just as with James Cole (Bruce Willis) in Terry Gilliam’s 1995 film Twelve Monkeys (which I discussed in an earlier post), Paul’s visions of his own future influence his choices, suggesting that they were never his in the first place. Paul is the One. It is not his choice; it is his calling, and he must answer.

In keeping with this post’s exploration of futuristic visions and predestination, my next post will be on Villeneuve’s other sci-fi masterpiece: the mind-bending Arrival (2016). Make sure to check it out!

Recent Comments