When I first watched this film, it reminded me of an American stage play called A Streetcar Named Desire (1947). While the plots have no similarities, the themes are similar, portraying a slow descent into madness created by longing and the past’s torture. Muriel, or The Time of Return, directed by Alain Resnais in 1963, is the follow up to Last Year at Marienbad (1961). I haven’t watched the former, but since the storylines do not follow each other, I was able to watch this film on its own (and so can you). However, both films do discuss the nature of time and how memories can haunt you forever.

The film follows multiple stories and sometimes gets a little confusing. We meet Hélène (Delphine Seyrig) and her stepson Bernard (Jean Baptiste Thiérrée), who has just come back from fighting in Algeria due to the conclusion of the French-Algerian war (1954-1962). Hélène meets an old lover from before her late husband named Alphonse (Jean-Pierre Kerien) and his “niece,” Francoise (Nita Klein), whom we later find out is actually his young lover. Both Alphonse and Hélène are plagued with memories of longing for their relationship that happened long ago, but due to time and separation during World War II, they now feel distant. Bernard has trouble recuperating from a traumatic event he experienced in Algeria, separate from the war. All of the entangled storylines force our curiosity, our minds trying to make connections between them as we watch each story unfold. However, we are never given the confidence of knowing exactly where each character’s story will lead, which then limits us to merely watching the film as it goes on, even through the awkward silences, the unfinished sentences, and the questions without answers. On top of that, the sound track is very eerie and a repeated, spooky angelic voice sings extremely high pitched notes throughout the film. By doing this, Resnais truly gets an authentic reaction out of his audience – when they aren’t thinking about the ‘what ifs’ in, or about, the film.

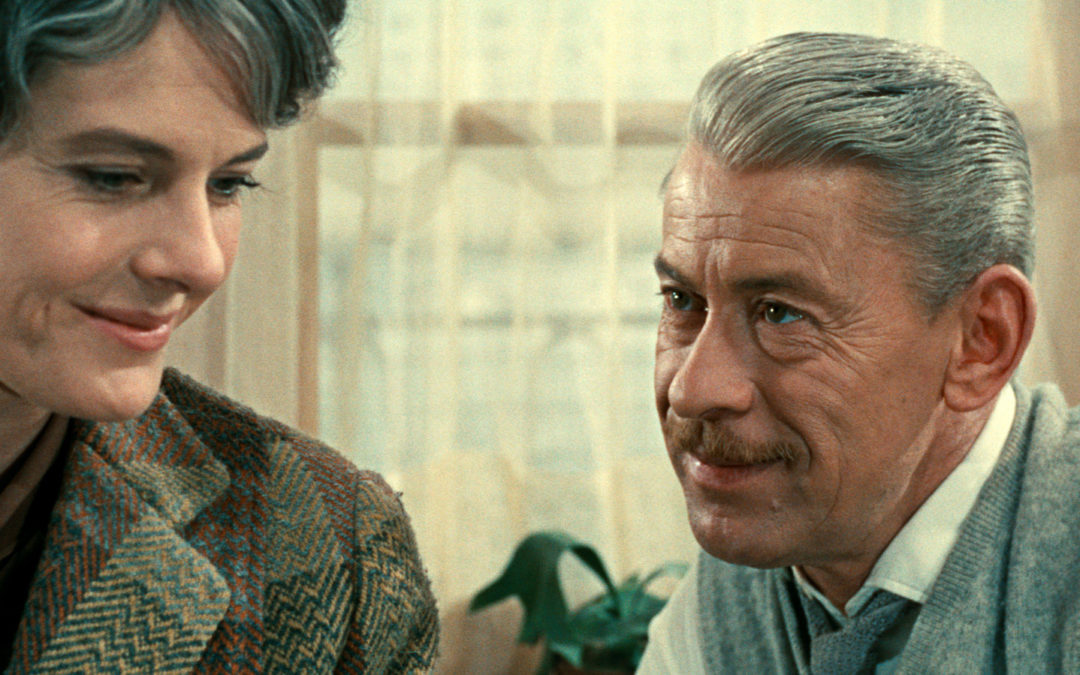

An awkward glance from Françoise (Nita Klein) across the diner table.

Unlike Resnais’ other films like Hiroshima mon Amour (1959) and Last Year at Marienbad, in which the protagonists don’t have names, these characters finally do. I think the plot would be too confusing if there weren’t names included in this film, honestly. On the other hand, Resnais plays with the idea of time in all three films. In Hiroshima Mon Amour and Last Year at Marienbad, both moved back and forth between the past and the present by using flashbacks. However, this film does not utilize flashbacks. Instead, the characters only discuss the past, and the anguish they feel is evident on their faces. We have to look at each storyline objectively because unlike Hiroshima Mon Amour, which places us directly in the unnamed woman’s shoes (Emmanuelle Riva) by showing us her flashbacks, we only get the vague details of what each person’s past was like through their conversations. Possibly the only images of the past we receive in this film are videos of the Algerian war, assumably taken by Bernard himself.

Hélène’s (Delphine Seyrig) in evident anguish.

As I mentioned, Bernard has trouble coping with an incident he saw happen in Algeria. This incident involved an Algerian woman named Muriel, but we never see her throughout the film, even as he describes the torture she was put through. It is this torture – her torture – that haunts him. The memory of her death is still so vivid for Bernard because his story talks about how he remembers her lips, eyes, and bodily fluids, describing her body as “a sack of potatoes split open” (Muriel). Her name wasn’t Muriel due to her Algerian roots, but it is the name the rest of the French soldiers that tortured her gave to her to associate her with a culture they could understand: their own. Bernard did not take pleasure in seeing her lifeless body or how his comrades treated her. Due to that, when he returned home, he killed his friend who took part in the torturing, then left Hélène and his fiancée to do some soul-searching. In both of Resnais films I’ve seen, he pays tribute to particular wars or tragedies somehow. In Hiroshima, he shows the real-life footage of the carnage from the bombing, and in this film, I believe Muriel represents more than herself; she represents all of the suffering that came from the French-Algerian war.

The film’s location takes place in the city of Boulogne-sur-Mer near the seaside, which is located in the very north of France. The city itself has remnants of the past too, as the city was bombed during World War II, and most of the architecture had to be re-built. The film discusses this because one of Hélène’s other assumed recent lovers, is an architect specializing in redoing war-laden buildings, but many of the new buildings are bland and tasteless. This is similar to the on-going theme in the film of how time changes people, becoming someone entirely different. Even Hélène’s apartment is mismatched and scattered, and as an antique furniture seller, most of her apartment is full of different antique pieces that don’t really compliment each other. She even personally uses pieces she is going to sell sometimes, like a set of plates she uses to feed Alphonse and Françoise.

Hélène’s mismatched apartment with Alphonse (Jean-Pierre Kerien) standing to the right side.

Explicit fragmentation in the film was significant to Resnais because, during the early 1960s, modernity was starting to shift the aesthetics of homes, clothing, literature, and art — this shift also included films, and he wanted to capture that change. The movie’s editing is very fragmented but in a montage style involving everybody’s personal stories as they go about their day. For instance, we will see Alphonse going to different businesses and talking with various people in every new shot, or we’ll see Hélène going to get her nails done or going to the casino. Another excellent example of fragmentation is in the very beginning of the film when we are presented with shots of the furniture around Hélène’s house, but they happen so rapidly that it’s hard to grasp precisely what the image was. Even the dialogue is separated sometimes by not finishing sentences, or the shots of people talking are mismatched to who they are talking to. By the end, there are too many secrets that are revealed and memories that can no longer be held down, leading to everyone leaving each other even though they wanted to act like everything was okay on the surface.

Alain Resnais films are unique and quite different from other French New Wave films we’ve discussed throughout each issue. They don’t follow linear storytelling, and compared to the Godard film in this issue that plays with our belief in what is real or not, Resnais sets up expectations in relation to the past, present, and future, but not the world that surrounds the characters. Compared to other New Wave films, his films are the only ones that play with time, but not reality.

Resnais was part of the Left Bank group that arose in the late 1950s and early 60’s, much later than when directors like Truffaut or Godard had started. The difference between the group of Cahier du Cinéma directors and Left Bank directors was that Left Bank directors found more joy in documentary practices or other art forms than cinema. Sometimes, the Left Bank group is regarded as the ‘second wave’ of the Nouvelle Vague. While the other filmmakers sought to use film as their personal way of portraying the world, Left Bank directors wanted to portray the world from an objective perspective. Resnais also worked with Agnes Varda on the film La Pointe Courte (1955). They were close friends, and Varda was considered part of the Left Bank Group as well. Resnais’ first 1956 film, Nuit et Brouillard, or Night and Fog, is an almost-thirty-two-minute documentary on German concentration camps. The documentary was not made out of a personal reason but was commissioned, as was Hiroshima. You can probably tell by now how much Resnais loved to look into the past and respectfully acknowledged the loss and pain that these events caused. The return to memories that were once forgotten are what many of his films center on, because sometimes, it’s the recollection that hurts and brings more clarity than the actual memory itself.

Recent Comments