Trigger warning: The film contains disturbing images and utilizes a decent amount of fake blood and profanity that may be offensive.

As a child, I never watched Alice in Wonderland (1951) and still haven’t watched the 2010 version or its sequel, but Jean Luc-Godard’s 1967 film Weekend certainly makes a good substitute. This film’s plot has similarities that could represent the R-rated version of the children’s novel, Alice in Wonderland. Godard presents destruction, politics, hatred, and separation in Weekend, all while falling deeper down its own rabbit hole.

By the time the film came out in 1967, France was in the midst of political protests and social turmoil. Godard — known for his radical ideas — used this film to display the tension in the air. Weekend is very similar to Godard’s 1966 film Masculin Feminine, which depicts how the younger generation in French Society was affected during the Cold War. However, this film had a very radical political message, this time about the effects of the Vietnam War and social uprising.

The film uses inter-titles, just like Masculine Feminine did, but they are more inconsistent and random this time around. Some of the inter-titles are colored with red, white, and blue, relating to France’s flag colors. Just as our U.S. red, white, and blue flag has lost its initial meaning over time and throughout many wars, the ideologies that the stars and stripes represent have morphed depending on the generation, and especially with the recent presidential election — have been given new light. Likewise, the colors for France’s flag represented something more expressive for vigilant individuals who were beginning to question the French government. Some of the inter-titles follow patterns that are reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s pop-art. Parallel to what the film’s message is about, pop-art took everyday objects of society that were familiar and changed them through repetition and irony, becoming satirical figures of the unforgiving capitalist society most countries live in.

An inter-title in the film that resembles Andy Warhol’s pop-art.

While the film carries a lot of political connotations, the storyline is quite hectic in itself. The film starts with a bourgeoisie couple by the names of Roland (Jean Yanne) and Corinne (Mireille Darc) Durand who plan on murdering Corinne’s father and mother to inherit their wealth. On their way to her parents’ house, they encounter several obstacles that stop them from reaching their destination. Godard was hesitant to use both actors since they worked in mainstream cinema — especially Darc, since she was well known for more sexual roles — and had never done any New Wave films before, but I think they fit the parts quite well.

The film’s violence and carnage is hard to turn a blind eye to from the very start. Within the first two minutes we see a man get beat up and left on the hard concrete ground. After that, we are told a very erotic story from Corinne about how she was trapped by a couple, forcing her into a seemingly unwanted threesome. With the film immediately implementing such brash images, burning into our brains, we are wary of what’s to come next – but, in a sense, we are simultaneously ready for it, knowing that the violence will have substantial implicit meaning. Other hard-to-watch scenes include a woman being burned alive, a shameless stabbing, implied cannibalism, and tons of car crashes. If you have a weak stomach or aren’t fond of violence, you might have difficulty watching this film. With all of the car crashes, making the beautiful countryside and small towns seem like an apocalyptic wasteland, the cars’ representation became something much different from Godard’s first film, Breathless (1960). In Breathless, Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) steals every car he can get his hands on, but they represent liberation from the grasp of how society tells us to live. Yet, in this film, the cars are now broken, deteriorating, and up in flames. The pile-ups can be compared to how French society has become suffocating and broken as time went on.

One of the most powerful and well-known sequences of Weekend is the traffic jam scene, intermingled with inter-titles to give the appearance of one long tracking shot. Lasting nine minutes, this sequence follows Roland and Corinne in their car while they are trying to weave their way into a long line of traffic. As the camera trails the couple, we see other people playing catch, enjoying a picnic, or playing chess while waiting in their cars. As Roland tries to bud into open spots, he gets backlash from others who have remained there all day. When they finally get to the end, we see the cause of the jam, a pile-up involving multiple cars with dead bodies strewn about the road, grass, and doused in blood. Godard commented on this sequence, saying, “Politics is a traveling shot”. In my interpretation, I believe the sequence represents that politics only become more convoluted and jam-packed as time goes on, affecting our society and way of living in turn; in the end, is it all worth it?

A couple playing chess as they wait for the traffic jam to clear up.

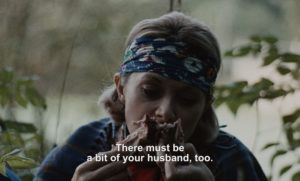

You’re probably wondering why I mentioned Alice in Wonderland when seemingly everything I’ve talked about so far has nothing to do with anything from the novel’s plot. To clarify, the film has been compared to the book due to its continuous strand of problems or people that the couple comes across. Plus, Godard makes a direct reference to Lewis Carroll in an inter-title saying, “The Lewis Carroll way” – Carroll being the author of the children’s book. There is also a scene where the couple comes across a man and woman dressed like the novel’s characters, only talking in rhymes and trivia. By the end, Roland and Corinne are successful in achieving her family’s inheritance by murdering her mother — since her father finally died after years of slowly poisoning him — but are captured by a band of hippies who survive off of cannibalism. Roland tries to escape but is chopped up by the group and eaten by Corinne who became the leader’s lover to survive. Such strange experiences and scenes like these constantly tear apart the film’s reality that we had been led to believe to be true through the use of inter-titles, fast cuts, or setting up our expectations. But, these scenes just show there is no guarantee of what’s to come next.

Corinne (Mireille Darc) “eating” cooked parts of her husband.

While the French New Wave movement is regarded as one that has changed the course of cinema forever, and Godard and Truffaut films being considered the dominant forces, the movement shouldn’t be bound to just those two names. Instead, it should be looked at more broadly, putting anyone who used the approaches the movement created in just as high of regard. We’ve looked at other directors like Jacques Demy or Chris Marker who, while not as prominent in the movement as some of the beginning French New Wave directors from Cahiers du Cinéma, still utilized the idea that film can be whatever they wanted to make it.

The postmodern techniques that tear us away from reality or place us into hyper-realities, like fast cuts or long shots that Godard used, illustrate a bigger picture of personal freedom. This also granted Godard the title of an Auteur as well. Godard’s films have changed over the years just as France changed as a country, evident in the difference between Breathless, Weekend, and the in-between, Masculin Feminin. Godard led the way for the film movement to flourish and exemplified the freedom that comes with the New Wave techniques from traditional cinema, but his use of radical ideologies and symbolism in his films shouldn’t be the only defining factor while discussing the movement. There are tons of ways that the movement can be looked at, such as through different styles of New Wave films, like Playtime or Purple Noon. Weekend is the second-to-last Godard film we’ll look at – Godard’s Tout va Bien being the last film from him in my next and final New Wave issue – and is entirely deserving of its spot in my New Wave issues, even though it is certainly not for the faint of heart (or stomach).

Recent Comments